Acceleration of Self-Care in the Time of COVID-19

What is the context?

The need for fundamental transformation in our health systems has never been more apparent. Already the world faces a shortage of 13 million health workers. Now, in the context of COVID-19, our dependencies on a stretched health workforce are brought to the fore, demanding creative, urgent, and difficult solutions.

People are asked to steer clear of COVID-19 hotspots such as hospitals and clinics, to use telemedicine or hotlines where they exist, to self-diagnose using symptom guidelines, and to self-medicate. Preventative and curative care jostle together, both equally important, both challenged to be delivered in tandem. World over, millions volunteered almost overnight to support continuity of health services, with clinicians coming out of retirement, and others lending their non-clinical expertise and labor. At individual, community, and health system levels, we are witnessing an overnight transformation in how people use and organize healthcare.

[ss_click_to_tweet tweet=”For COVID-19, self-care requires a carefully choreographed set of interactions between health workers and individuals to enable people to take greater control over their healthcare.” content=”For COVID-19, self-care requires a carefully choreographed set of interactions between health workers and individuals to enable people to take greater control over their healthcare.” style=”default”]

As COVID-19 moved from outbreak to epidemic and now pandemic, and with the significant possibility that for the next 18 months we see episodic outbreaks of COVID-19, one immediate need—and potentially lasting health system transformation—will be learning what services and information can be provided with less dependency on health workers.

These measures are both to protect heroic frontline health workers, but also to ensure the most effective healthcare can be provided at scale. In this context, self-care is not only occurring, but has rapidly become a critical answer in the health system response to COVID-19.

What is self-care?

For the uninitiated, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines self-care as “the ability of individuals, families and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a healthcare provider,” and add in subsequent publications that “self-care interventions are among the most promising and exciting new approaches to improve health and well-being, both from a health systems perspective and for people who use these interventions.”

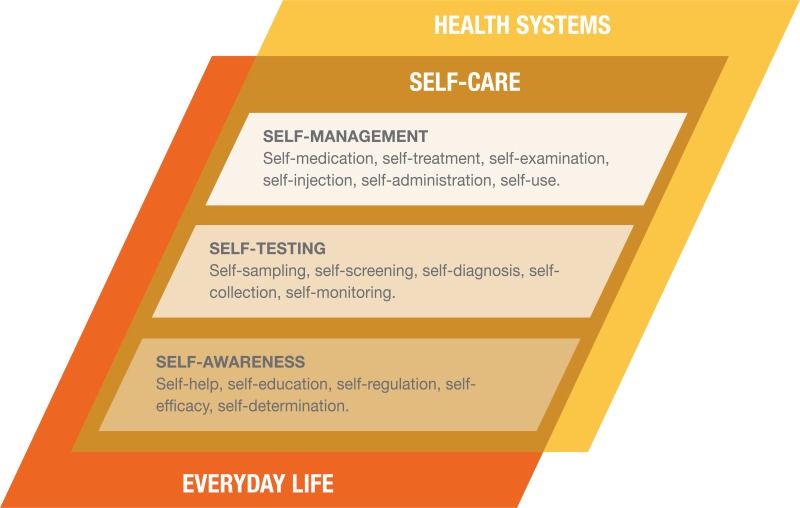

Figure 1. Self-care in the context of interventions linked to health systems.

Prior to COVID-19, self-care was already increasing in relevance for health systems. This is not self-care focused on general physical and mental wellness, although self-care does incorporate those broader and important considerations. This is self-care in the form of drugs, diagnostics, devices, and digital health, that—paired with growing demand by individuals for participation in their healthcare—has led to a greater configuration of self-led health care possibilities than ever before. Information, products, and services previously requiring the full participation of health workers have seen individuals take greater responsibility for their health care. Examples of this abound across the range of self-management, self-testing, and self-awareness (see Figure 1).

Prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, health systems from Uganda and Nigeria were working on plans to take the 2019 WHO Consolidated Guideline for Self-Care Interventions in Health for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights and other self-care interventions to scale. This specific WHO guideline recognizes that many evidence-based practices within the SRHR space could be promoted to enhance self-care, and recommends measures such as HIV self-testing, HPV self-sampling, and self-administered injectable contraception all be available at scale.

Why is self-care important in the context of COVID-19?

Within a COVID-19 response, self-care is how we help one another, and what keeps our health systems from complete collapse. It appears in our efforts to self-screen through AI-powered websites where we check how common our symptoms are in relation to COVID-19, or in those WHO WhatsApp alerts used to self-educate. It’s the promise of home self-testing (tantalizingly close), and all we do to care for ourselves and our household when someone falls ill.

This sudden and rapid reliance on self-care isn’t how we imagined it—haphazard and driven out of crisis rather than thoughtful health system design. There will be people now managing their health in ways that they should not, cannot, be expected to do alone. In this messiness exist dangers and pitfalls, such as the general public and physicians purchasing and using chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine after recent reports suggested they may be able to treat COVID-19, but with insufficient evidence or reflection on the consequences. The safeguards (financial protection, safe and quality care, adequate support from a health worker when needed) have not been fully established.

But crises don’t wait for us to get it right, as much as they reveal how previously we could have done things differently, better. This leaves us in a transitional moment, where the rapid transformation happening cannot be ignored. Within the lens of outbreak response itself, self-care plays an important function. Self-care will also remain important for the many healthcare needs that carry on regardless of COVID-19. And it will play a critical role in the health systems that exist once the pandemic has subsided.

What does advancing self-care look like?

Self-care can mean better, more accessible, participatory, affordable, quality healthcare. In the case of the emergency contraceptive pill or acetaminophen when available over the counter, such self-care will require minimal or no interaction with a health worker. However, frequently, for COVID-19 and many health interventions, self-care requires a carefully choreographed set of interactions between health workers and individuals to enable people to take greater control over their healthcare.

As the WHO guidelines also highlight, self-care is not a binary phenomenon of healthcare worker versus person-led healthcare, rather it’s far more dynamic. For example, the HIV self-test may be taken alone but requires referral into the health system for result verification and treatment, if needed. HPV DNA self-sampling allows a woman the control and privacy to collect her own specimens for screening for cervical cancer, but the health system will review the results and assist clients to interpret and act on them, including treatment when applicable. Self-injected DMPA-SC and oral PrEP for HIV prevention might require an initial contact with a pharmacist, clinician, or lay health worker, but are largely used autonomously thereafter—with support provided at intervals to counsel through any adverse effects and adapt regimens or switch methods as needed. The nature of these interactions will vary by intervention, by population, and across people’s lifetimes.

What can we do?

During the COVID-19 outbreak and beyond, a health system that optimized self-care would therefore consider the following:

- It would be designed around continuity of care, including self-care, acknowledging that connections to the health system will often remain and need to be fit for purpose: robust enough to ensure clients receive quality healthcare, yet flexible enough to ensure clients are not prevented from accessing the better healthcare that self-care can provide. Continuity might include use of digital health solutions, such as those being used now to support users at home while protecting healthcare workers from COVID-19.

- In addition to a continuity of care approach, such self-care will keep a systematic approach to safety and quality of care front of mind, with processes to ensure technical competence of health workers and people in the delivery of self-care, of client safety and satisfaction, quality information and interpersonal exchanges. The unique role of credible and trusted information is also critical, to address rumors, myths, prevent dangerous practices, and promote good practices.

- It would recognize the role of health system actors in promoting and advancing self-awareness—with healthcare workers and individuals not on parallel tracks towards health, but in partnership with one another. This requires healthcare workers take an active role championing health literacy, self-awareness, and promotion of self-care where appropriate. When we’ve been conditioned to view ourselves as recipients of healthcare, it will take healthcare workers to help us shift that paradigm.

- Self-care should also keep universal health coverage top of mind, so that access, quality, and equity are not overly compromised amidst the rapid transformation health systems face with this pandemic. In particular, financing of self-care will require as extensive discipline as is applied to the financing of existing health systems, precisely because self-care is a health system solution.

Self-care, enabling people’s own capacity to do what once relied on healthcare workers, would have been one part of the future of healthcare regardless of COVID-19. But to navigate COVID-19 and come out with health systems and public health capacities that are stronger—not further fragmented—it’s increasingly important to find the balance between self-care and what we rely on healthcare workers and health systems to deliver. To the extent possible, documenting and reflecting on this rapid transformation will also be crucial to learning from this. And if there is one ray of hope in challenging times, it is that through necessity, quality self-care may become better organized, resourced, and applied. People, together, can do this.

About the authors

This work is co-authored by staff from PSI and Jhpiego. Both organizations are rapidly employing existing and new resources to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as ensure existing health system capacity is maintained in critical health areas. Through the Self Care Trailblazers Group, generously supported by the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (UK) and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, both PSI and Jhpiego benefit from the collective wisdom and momentum of many organizations working in self-care at global and country level, from FHI 360, PATH, White Ribbon Alliance, IPPF, the Self Care Academic Research Unit at Imperial College London, Johns Hopkins University, SH:24, EngenderHealth, Aidsfonds, Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) and many others. The technical leadership and support of the World Health Organization has also been vitally important to strengthening the emerging self-care movement, alongside the growing support from the USAID Office of Population & Reproductive Health, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the UK Department for International Development.