A mudança mais significativa é útil para avaliar a gestão do conhecimento? 5 coisas que aprendemos

Da capa do guia “The Most Significant Change (MSC) Technique” de Rick Davies e Jess Dart.

A técnica de Mudança Mais Significativa (MSC) — um método de monitoramento e avaliação com consciência da complexidade—baseia-se na coleta e análise de histórias de mudança significativa informar gestão adaptativa dos programas e contribuir para a sua avaliação. Baseado em Conhecimento SUCESSOexperiência de 's com o uso as perguntas do MSC em quatro avaliações de iniciativas de gestão do conhecimento (GC), nós descobriram que é uma forma inovadora para demonstrar a impacto do KM em os resultados finais que estamos tentando alcançar — resultados como adaptação e uso do conhecimento e programas e práticas melhorados.

Como praticantes de gestão do conhecimento (GC), muitas vezes nos perguntam por que o planejamento familiar e a saúde reprodutiva (PF/SR) e outros programas de saúde pública devem investir em intervenções de GC. Especificamente, as pessoas querem saber que tipos de resultados eles podem esperar alcançar investindo em KM. Demonstrar o impacto do KM em resultados de nível mais alto — como usar dados e informações para informar a tomada de decisões de programas ou políticas ou aplicar conhecimento para melhorar os sistemas de saúde — pode ser desafiador porque pode ser difícil extrair o impacto específico das ferramentas e técnicas de KM quando elas são usadas em conjunto com outras atividades de saúde pública.

É aqui que monitoramento e avaliação com base na complexidade Os métodos (M&E) entram em cena. Usamos as perguntas do Mudança mais significativa (MSC) — um método de M&A com base na complexidade — para contribuir com a avaliação de diversas iniciativas de GC que lideramos e descobrimos que é um método útil para demonstrar os benefícios (resultados) dessas intervenções de GC.

O que é MSC?

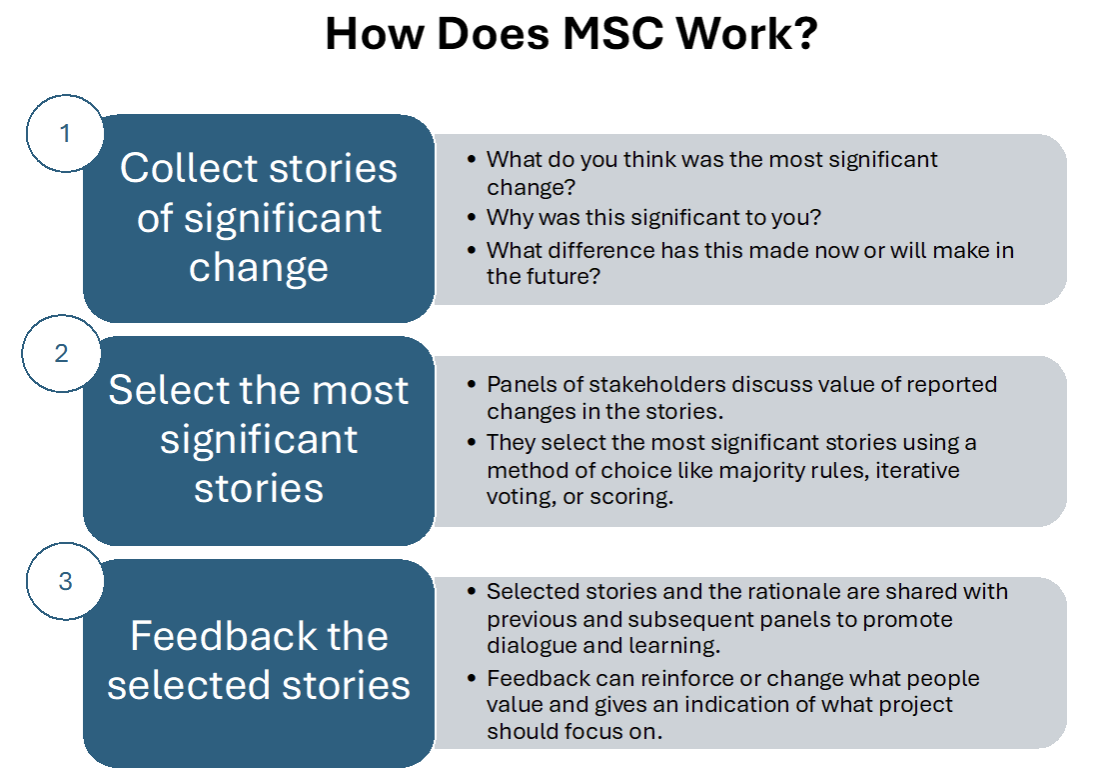

O MSC é um método participativo de M&A baseado em histórias em vez de indicadores (veja a figura). Ele foi projetado para ser usado durante todo o ciclo de vida de um projeto para informar correções de curso contínuas (em outras palavras, para monitoramento contínuo e gerenciamento adaptativo), mas também pode contribuir com dados qualitativos sobre os resultados e o impacto de um projeto.

As histórias do MSC são baseadas nas respostas dos entrevistados a três perguntas principais do MSC:

- Qual você acha que foi a mudança mais significativa?

- Por que isso foi significativo para você?

- Que diferença isso fez agora ou fará no futuro?

As perguntas, à primeira vista, parecem simples — talvez até simples demais! Mas, como usamos as perguntas do MSC em avaliações de iniciativas de KM tão diversas quanto a nossa Programa Círculos de Aprendizagem, O campo, nosso Intervenções de fortalecimento da capacidade de GC na Ásia e na África Oriental, e a nossa parceria com cinco países africanos francófonos para integrar KM em planos de implementação custeados (CIPs), descobrimos que o MSC é realmente poderoso!

Cinco lições que aprendemos sobre a MSC

1. As perguntas do MSC são bastante poderosas, permitindo que diferentes perspectivas surjam de experiências diversas.

Estávamos nervosos sobre usar apenas as perguntas do MSC em nossas entrevistas e grupos focais. Não achamos que obteríamos dados sobre certos resultados (positivos ou negativos) porque as perguntas do MSC eram muito amplas, então também fizemos perguntas mais específicas aos nossos entrevistados. Descobrimos que as respostas das pessoas às perguntas mais específicas eram geralmente duplicadas do que elas tinham compartilhado nas perguntas do MSC e, às vezes, menos ricas.

Por exemplo, em resposta às perguntas do MSC, um participante dos Círculos de Aprendizagem Africanos Francófonos compartilhou:

Particulando nisso [Círculos de Aprendizagem] a sessão me permitiu aprender novos conhecimentos e realmente teve um impacto na minha vida porque em primeiro lugar, nos permitiu conhecer novas experiências de nossos pares que estão em outros países. … através desta oportunidade, entendemos que existem práticas que existem em outros países mas que não estão em nosso país e … por que não duplicar essas belas experiências em nosso país também? … Oa segunda coisa … esta sessão permitiu-nos construir esta ligação e estas relações entre nós [participantes de outros países africanos]. E a terceira coisa é que nos permitiu aprender a gerir o nosso conhecimento. Porque é preciso dizer que fazemos muito no campo: fazemos atividades, fazemos iniciativas. Mas a sustentabilidade e especialmente a documentação dessas iniciativas — essas sessões nos permitiram, em todo caso, [aprender] a documentar e a gerir o corpo de conhecimento que podemos ganhar com as experiências.

Quando questionado mais especificamente sobre explicar se o formato dos Círculos de Aprendizagem foi útil para gerar e compartilhar lições sobre o que funciona e o que não no planejamento familiar programas, o mesmo participante referido de volta para aprender com as experiências de outros participantes como uma indicação da utilidade do formato dos Círculos de Aprendizagem:

Eu diria que o formato foi bastante útil em termos de gerenciamento, compartilhamento de aulas e programas, sobre o que funciona e o que não. … nos permitiu ver, por exemplo, aqui na Guiné, quais são os elementos ou quais são as iniciativas esse trabalho na área de FP? E o que não trabalho? Nós compartilhamos e outros jovens em outros países também compartilhadoe suas experiências.

2. As perguntas do MSC também ajuda descobrir resultados inesperados.

Formas estruturadas de M&E são úteis para caminhos causais lineares e claros. Mas em ambientes ou intervenções complexas, você precisa de algo com mais flexibilidade. Essa flexibilidade ajuda você a descobrir coisas para as quais você não necessariamente projetou. Depois de descobrir esses aspectos, você pode fatorá-los em seu design para fortalecer esses componentes ainda mais ou abordar áreas problemáticas.

Por exemplo, em nossa avaliação dos Círculos de Aprendizagem, ficamos agradavelmente surpresos ao saber de vários participantes que sua participação nos Círculos de Aprendizagem contribuiu para seu avanço na carreira, algo que não havíamos considerado intencionalmente no design inicial do programa:

Posso ver isso [os Círculos de Aprendizagem] como algo muito bom para minha carreira, a ponto de agora achar que estou indo para cargos ainda mais altos só por causa do conhecimento. – Participante da África Anglófona

“… Eu também fiz parte de toda essa rede regional e o impacto que [minha participação nos Círculos de Aprendizagem] criou foi que antes eu estava cuidando apenas da rede de nível indiano, mas depois de trocar os insights [dos Círculos de Aprendizagem] que forneci para a alta gerência organizacional, eles também me pediram para liderar essa rede regional do Sudeste Asiático. – Participante da Ásia

3. É eus útil para emparelhar os ricos dados qualitativos do MSC com dados quantitativos.

Descobrimos que as citações do MSC (e dados qualitativos em geral) fornecem descrições tão ricas das experiências das pessoas e um nível de compreensão dos resultados e impacto do trabalho que você está avaliando que você simplesmente não consegue obter com dados quantitativos. Também é bom, no entanto, parear os dados qualitativos com números e estatísticas, quando possível, para demonstrar até que ponto essas experiências e resultados podem ser representativos de um grupo maior de pessoas.

Por exemplo, em nossa avaliação dos Círculos de Aprendizagem, combinamos uma pesquisa mais tradicional de participantes com entrevistas centradas no MSC, descobrindo que a maioria 75% dos entrevistados da pesquisa disse que aplicou o conhecimento obtido nos Círculos de Aprendizagem para informar o design do programa, melhorias ou política. Nossas entrevistas com o MSC pintaram um quadro de como era a adaptação e o uso do conhecimento:

… como implementadora de um programa de saúde reprodutiva no Uganda, aprendi como poderíamos fazer uso das diferentes redes para fazer mais advocacy … Eu estava aprendendo com os participantes do Quênia como eles estavam fazendo isso do lado deles, especialmente usando as mídias sociais, como poderíamos identificar os principais atores para o planejamento familiar que também poderíamos utilizar em Uganda.

… Realmente me ajudou a mudar meu pensamento real, especialmente na programação sobre violência de gênero e agora posso entender melhor o que fazer em relação à violência de gênero, mesmo desenvolver propostas de financiamento, construir um caso mais forte dentro da minha organização para violência de gênero [programação].

4. Você ainda precisa experiente pesquisadores para coletar e analisar dados do MSC.

Embora as pessoas geralmente tenham entendido as perguntas do MSC e respondido adequadamente, ainda é importante ter entrevistadores experientes que possam sondar quando necessário. Uma vez que os dados são coletados, você também precisa de pessoas com alguma experiência em análise qualitativa de dados para analisar e sintetizar os dados. Usamos ATLAS.ti para codificar e analisar os dados, mas também estão disponíveis opções de software gratuitas e mais simples, como QDA Miner Lite, Taguette, ou mesmo Google Docs/Sheets ou Microsoft Word/Excel.

5. O MSC é um ótimo método para contribuir com a avaliação de intervenções de GC!

Nossa equipe teve experiência com o uso do MSC para monitoramento contínuo das intervenções do programa FP/RH sob a Iniciativa Desafio. Achamos que também poderia ser útil para M&E de intervenções de KM, mas não tínhamos nenhuma experiência ou evidência para apoiar esse palpite. Depois de usar o MSC em quatro avaliações de diferentes intervenções de KM, agora nos sentimos confiantes para encorajar outros praticantes de KM a experimentar o MSC!

Para mais informações sobre o MSC, não deixe de conferir estes recursos importantes: