Providing FP/RH Services in a Humanitarian Setting

Pathfinder’s Experience in Cox’s Bazar Bangladesh

Since 2017, the rapid influx of refugees to the Cox’s Bazar district of Bangladesh has put additional pressure on the local community’s health systems, including FP/RH services. Pathfinder International is one of the organizations that has responded to the humanitarian crisis. Knowledge SUCCESS’ Anne Ballard Sara recently spoke with Pathfinder’s Monira Hossain, project manager, and Dr. Farhana Huq, regional program manager, about experiences and lessons learned from the Rohingya response.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

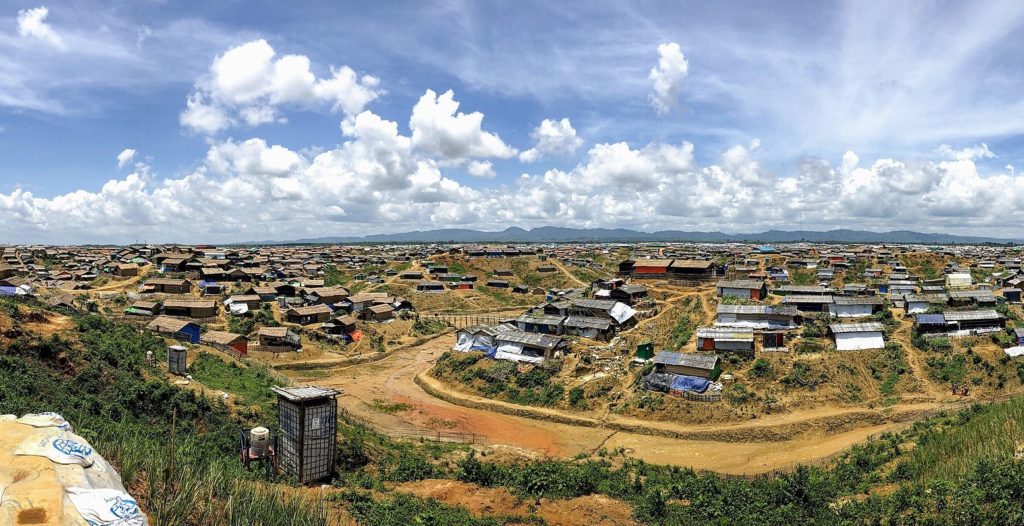

Since 2017, over 742,000 refugees have fled to Bangladesh to escape violence in Myanmar. This rapid influx of people, primarily to the Cox’s Bazar district of Bangladesh, has put additional pressure on the local community’s health systems. Many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are working to respond to this humanitarian crisis in the camps while strengthening the surrounding communities’ public health systems.

Pathfinder International is one of those NGOs. It has responded to the humanitarian crisis since the beginning of the influx in 2017. Pathfinder has specifically worked to improve the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of Rohingya women and girls in camp 22 within Teknaf Upazila of Cox’s Bazar, a region in the division of Chittagong, Bangladesh.

I recently spoke with Monira Hossain*, project manager, and Dr. Farhana Huq, regional program manager, about Pathfinder International’s response. In our conversation, we explore experiences and lessons learned from the Rohingya response and how they can inform the work of others addressing humanitarian responses around the globe.

Can you give us an overview of Pathfinder’s humanitarian work in the Cox’s Bazar district of Bangladesh as a response to the influx of Rohingya refugees?

Farhana: The Accelerated Universal Access of Family Planning (FP) project in Bangladesh is funded by USAID to strengthen the health system and FP services. We work with the Government of Bangladesh and with the Ministry of Health, including the Director General of FP, health nurses, and the midwifery system. We also work on a project with the Packard Foundation on menstrual health and menstrual regulation among adolescent girls living in the Rohingya camps as well as gender inclusion. We are implementing our activities in four divisions of Bangladesh—including Chattogram, Dhaka, Mymensingh, and Sylhet. Recently we’ve also incorporated additional activities for climate change and SRHR on another project funded by Takeda.

What is your overall objective?

Monira: Our goal is to improve SRHR for Rohingya women. We do that by focusing on SRHR (including maternal and child health services and FP), gender, and gender-based violence. We also engage the host community through field activities in the camps. We focus on these objectives to improve SRHR services for the Rohingya community but also provide services to the surrounding host community in Cox’s Bazar.

What is Pathfinder’s approach to serving the host community as well as the Rohingya community in the camps?

Monira: Most organizations working in Cox’s Bazar with the Rohingya people focus on the camps, but we also provide services to the surrounding host community. We provide SRHR services in the host community through public community clinics—part of the government structure—that serve 6,000 people. We have a strong relationship with the Director General of FP, which is a government agency, which makes our work easier.

How do you engage the Rohingya community to support the implementation of your activities?

Monira: In the camp setting, we use community health workers—also known as volunteers—that receive a daily payment to engage the Rohingya community and support effective implementation of SRHR services. They disseminate information, sensitize people, and describe the services available, including where and when to go. Ultimately, they motivate people, especially female clients, to seek FP and other SRHR services within the camps. We recommend this approach be used for effective implementation of any health project.

In your experience, what does an average day living in a Rohingya camp look like for someone living there?

Monira: The situation has changed. Back when the situation was declared a category 1 crisis worldwide, huge activities were happening here in Cox’s Bazar to accelerate all services, including health, nutrition and water, sanitation, and hygiene. That was a very traumatizing time for the Rohingya people. Their focus was to settle down in the camps and be introduced to Bangladeshi culture, the surrounding community, and the new camp environment. As time has gone on, the camps have developed and now all services and organizations are working under a common umbrella. So now, living in the camp is much more organized. People know where to get food, shelter, education, and health services, including FP. They are living in a more stabilized situation and are more accustomed [to] Bengali culture, and those working in the camps are now focused on mental health and disability inclusion in all services.

What is the average experience for accessing SRHR services for someone living in a Rohingya camp?

Monira: When they arrived [at] the camp in 2017, they were not very familiar with the full range of FP. The only methods they were familiar with [were] the oral contraceptive pill and the Depo. They were not aware of other modern methods and where they could access them and the importance of FP, so it was very challenging for all the organizations. Now, due to different organizations’ activities, it’s gradually improving.

Farhana: When the Rohingya influx began and they arrived in Bangladesh, many of them had a history of sexual violence, and they were pregnant unintentionally and struggling to find shelter. Many were not aware of and were not using an FP method as they came from very conservative backgrounds.

Monira: Inside the camps, short-acting methods and long-acting reversible contraceptive methods (LARCs), primarily the implant, are available. IUDs are not available due to a lack of skilled service providers at the health post, but there has been a change regarding behavior towards FP. It’s surprising [given their conservative background] that female acceptors have been interested from the beginning in LARCs once they came to know that these are also methods. They were very curious. However, taboos regarding religious beliefs and cultural practices are also there, so many organizations are working to overcome those challenges inside the camps.

What are your top three lessons learned regarding the provision of SRHR services to communities in crisis?

Monira & Farhana: The three lessons learned from this project are:

- Community participation is key to [achieving] successful implementation of an SRHR project and is also important for understanding the culture, stigma, and taboos in the community. This includes engaging influential leaders from the community to prime and lead conversations in local languages to help communities understand how the services provided can benefit them.

- Preparedness and mitigation plans in the Rohingya crisis—or any humanitarian setting—have to be kept up to date with emergency management and mitigation plans.

- Services should be provided from a common platform. All the different organizations and actors working in SRHR, health, or education should be working under one umbrella following the same standards. During a humanitarian crisis, there are several groups including SRHR groups, youth groups, menstrual hygiene management technical groups, etc. It’s important that they are managed under one umbrella for standardization, quality, and to monitor sustainability.

What do you hope SRHR services will be like in Cox’s Bazar five years from now? What do you think needs to happen in order for that vision to come to life?

Monira: Interesting question. Within five years, I can see SRHR services more organized for the Rohingya people and different organizations addressing more sensitive issues like gender and gender-based violence. Also, inclusion in regard to gender, age, and disability. Within five years, I hope to see an increase in facility deliveries and in child immunizations as well. I also hope there will be much more availability for treatments related to communicable and non-communicable diseases. And lastly, I am expecting that within five years, all health providers providing SRHR services specifically [emphasize] LARCs—not only for SRHR but for their general health overall.

Farhana: We would also like to see a decrease in the total fertility rate among the Rohingya people and the host community and an increase in the contraceptive prevalence rate and use [of] modern methods.

As you know, this response in the Rohingya camps is not new. So why do you think it’s still timely and relevant to talk about this topic?

Monira: Every day children are born inside the camps in different service centers or through home delivery. There is still a need to talk about this work because they are still living in the camps. Rohingya women and their children still have ongoing SRHR needs. We have to continue as long as they are residing in Bangladesh.

“Every day children are born inside the camps in different service centers or through home delivery. There is still a need to talk about this work because they are still living in the camps. Rohingya women and their children still have ongoing SRHR needs. We have to continue as long as they are residing in Bangladesh.”

What do you think others who are implementing FP/RH programs, who are working in similar contexts, can learn from your experience?

Monira: What other organizations can learn from Pathfinder’s experience is to do yearly eligible couple registration surveys. The result of the survey is a huge book with lots of information, including what methods they are accepting, method changes, and also information about food and nutrition. Once you do the eligible couple registration, it provides a complete picture of the situation to make FP implementation easier by helping you identify where to give more emphasis based on the needs. Other recommendations are to focus on male engagement, which still poses a challenge in the camps and host community. Finally, when you are implementing or designing any project, you have to keep in mind cultural acceptability, social taboos, and stigma and have a good plan to overcome those challenges prior to implementation.

Thank you so much for speaking with me. Do you have any final thoughts you’d like to share?

Monira: For humanitarian crises worldwide, I want to give a message from the Rohingya response that it’s very important to follow a standard for all services. And these standards are already available globally. I don’t have practical experience from other humanitarian crises, but I can say that for the Rohingya response in Bangladesh, they are maintaining a minimum service package for health [including sexual and reproductive health] that the government adopted very rapidly. It’s very challenging but possible. And it’s important to have these standards for sustainability and to maintain the utmost respect for the services we are providing for the Rohingya people.

Farhana: I am really encouraged that you are focusing on the Rohingya crisis. It’s important to hear these individual stories and voices in order to learn and see what to do differently for the next humanitarian crisis because—anytime—anything can happen, and we need to prepare. But of course, we are hoping the world will not experience any more crises.

Want to know more? Visit FP insight to view a collection of essential resources for FP/RH services during emergencies.

*Editor’s note: Since this interview occurred, Monira has left Pathfinder.