A Life-Course Approach to Reproductive Health

Who Are We Leaving Out?

Older adults (those over the age of 60) not only represent a large portion of the world population, but they will continue to do so for the next 30 years. While growth in this age group is fastest in Europe and North America, the number of older adults will increase in every region. Despite this, reproductive health programming often fails to include middle-aged and older adults in its intended audiences and neglects to answer the question: What happens to reproductive health services as people age? Are current approaches to implementing sexual and reproductive health across the life course effectively addressing changing demographics?

Interested in the importance of reproductive health integration into broader SRH programs? Read the companion piece: a Q&A with TogetHER for Health and PSI.

As of 2017, there were an estimated 962 million people over the age of 60 around the world. By 2050, the number of people in this demographic is expected to reach 2.1 billion, keeping pace with the projected number of adolescents (2 billion). The third Sustainable Development Goal strives to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” through several objectives including universal access to sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services. SRH must be a central part of people’s lives as they age. Addressing health and well-being at all stages of life is essential to the overall welfare of societies.

Impacts of a Life-Course Approach to SRH

Reproductive health needs and desires are dynamic over time—the current life-course approach was created to respond to these changing needs. The life-course approach framework to reproductive health was intended to consider the reproductive health needs and desires of people over time, across the various life stages, including:

- Pre-pregnancy.

- Pregnancy.

- Infancy.

- Childhood.

- Adolescence.

- Reproductive years.

- Post-reproductive years.

However, in practice, the implementation of the approach has been uneven, focusing the majority of attention and resources on the beginning life stages. This was to the detriment of older adults despite the importance of ensuring all people of all ages are their healthiest selves. Additionally, specific evidence shows that older adults experience interpersonal violence (IPV), sexually transmitted infections, and a higher risk for cancers of the reproductive organs.

The adolescent and youth life stage is formative—people define and solidify their core values, make important life decisions, and develop cognitively and neurologically. Similarly, the young adult stage of life is also usually when people make important life decisions, such as when and how to have children. Therefore, many programs and resources focus on these two stages of life. However, with more and more women delaying marriage and childbirth around the world (and the fact that a sexual life does not end when one’s reproductive years end) focusing on middle-aged and older adults is important.

Key SRH Needs Across a Woman’s Life

Childbearing has a significant impact on individuals. For many women, these births happen relatively early in their lives. However, in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa (where fertility rates remain high) women have children spread out across their reproductive years, with higher birth order at older ages. In addition, in much of North America and Europe, a growing number of women are delaying having children. The median age at first birth has risen to 30 years old, with subsequent births occurring into a woman’s 40s and 50s. Therefore, prevention of pregnancy remains a need until menopause. Their preferences, priorities, and experiences related to family planning (FP) are often excluded from research and service provision. The FP needs and preferences of older men are similarly ignored.

Many adults continue their sexual lives well into older adulthood. An estimated 80% of men and 65% of women remain sexually active in old age. Both men and women experience changes related to their sexual health including the effects of menopause and decreases in testosterone. Older women, in particular, are at a unique risk of HIV infection due to the effects of menopause (decrease in lubrication, vaginal dryness, and the atrophy of the vaginal wall).

Furthermore, older adults are largely not using condoms (currently the only contraceptive to protect against both birth control and STI transmission) since they do not need them for birth control. Due to these biological and behavioral factors, older adults have significant rates of STI transmission and are diagnosed later in the course of HIV infection than younger people.

Every year approximately 100,000 people over the age of 50 acquire HIV. Seventy-four percent of this population lives in sub-Saharan Africa. Outside of transmission risks, adults over the age of 50 face unique considerations in treatment. While people over the age of 50 are more likely to remain on antiretroviral therapy (ART), older adults are less likely to respond to traditional ART. Management of HIV becomes more difficult as older adults develop more non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and hypertension.

Credit: Yagazie Emezi/Getty Images/Images of Empowerment.

The risk of different forms of reproductive cancer (breast, cervical, ovarian, uterine, prostate) also increases with age. Prostate cancer is the world’s second-most diagnosed cancer and is the leading cause of cancer death in 48 countries, many of these in sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and Central and South America. In women, breast cancer and cervical cancer are the two most common cancers. Breast cancer accounts for 1 in 4 cancer cases and 1 in 6 cancer deaths worldwide. Some of the most rapid increases in breast cancer incidences are occurring in sub-Saharan Africa. Cervical cancer is the world’s fourth most frequently diagnosed and is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in 23 countries. It is the leading cause of cancer death in 36 countries—many of them in sub-Saharan Africa, Melanesia, South America, and Southeast Asia.

Cervical cancer is considered a highly preventable form of cancer. Highly effective prevention measures include:

- Vaccination against Human Papillomavirus (HPV), an STI that can lead to lesions on the cervix that develop into cancer usually later in life.

- Regular cervical screening.

- Timely follow-up of abnormal findings.

However, due to decreases in screening, incidence rates have climbed worldwide (most notably in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa). In fact, only 44% of women in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have ever been screened for cervical cancer. This signals a significant disparity in access to preventive services, which also leads to higher rates of disease and mortality. In Kenya, nine women die each day from cervical cancer, while only 16% of eligible women report ever being screened for the disease.

While the increased risk of certain types of cancers has been well recognized by providers and health education campaigns, STI risk among older adults is poorly understood and addressed due to several factors, including:

- Provider and public health bias.

- Insufficient policies.

- Harmful social and cultural norms that perpetuate ageist beliefs about the sexual health of older adults.

In terms of primary prevention, the HPV vaccine is relatively new. It was only approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2006 and targeted children and adolescents (9–13 years). For these reasons, a large proportion of adults have never been vaccinated against HPV. As of 2020, less than 30% of LMICs had a national HPV vaccination campaign.

Ageism refers to the stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination directed towards people based on their age. In a newly launched report, the WHO and the UN outline the nature and impact of ageism on several facets of life, including health areas such as sexual and reproductive health.

Cancer of the reproductive organs and its required treatment can have an impact on a woman’s ability to have children. Depending on when she is diagnosed and the level of treatment required, some women make the difficult decision to have a hysterectomy or radiation, leading to immediate menopause.

Impact of Social and Cultural Norms

In many contexts, social norms and cultural beliefs support harmful ideas about the sexual lives of older adults. Often, the prevailing belief may be one of disbelief: the idea that older adults do not even have sex. This does not reflect reality. In a study conducted in southwestern Nigeria, adults 50–75 years old expressed the importance of sexuality in older age, with both physical and spiritual consequences. In a study examining 29 countries, results indicated that sexual desire and activity are pervasive in middle age and continue into older adulthood.

Even if people accept that older adults have sex, they are not expected to speak about their sexual lives. These social norms and cultural beliefs manifest themselves through policies that overlook the inclusion of older adults in sexual health programming and provider and health worker bias in patient interactions.

General sexual and reproductive health policies often do not include specific provisions for reaching older adults, as they do with adolescents and youth, and there is limited to no inclusion of older adults in the decision-making process, beyond the policymakers that may be present. And, in some cases, free access to SRH services under national programs ends once a person reaches a certain age.

Furthermore, in interactions with providers and other health workers, older adults may not feel comfortable bringing up the topic of SRH, and providers assume SRH isn’t relevant to older patients.

Finally, there are limited to no campaigns or sexual health education targeting older adults, leading to significant gaps in sexual health information among this population.

What Are Programs Doing to Address These Gaps?

Cervical cancer programs are uniquely positioned to address women’s reproductive health needs over the course of their lives.

Cervical Cancer Programs

(hover for details)

TogetHER for Health

TogetHER for Health is an advocacy organization that works with partners and other stakeholders to mobilize a global movement to end cervical cancer deaths.

Find out more about its Kizazi Chetu (Kiswahili for “my generation”) campaign.

Integrating Cervical Cancer Prevention Services

PSI along with Marie Stopes International, the International Planned Parenthood Federation, and the Society for Family Health integrated cervical cancer screening and preventive therapy into voluntary FP programs.

Explore best practices from this program.

The Global Initiative Against HPV and Cervical Cancer (GIAHC)

GIAHC aims to empower people, communities, and societies internationally to reduce the disease burden from HPV and cervical cancers through collective engagement, advocacy, collaboration, and education.

Learn more about this exciting initiative.

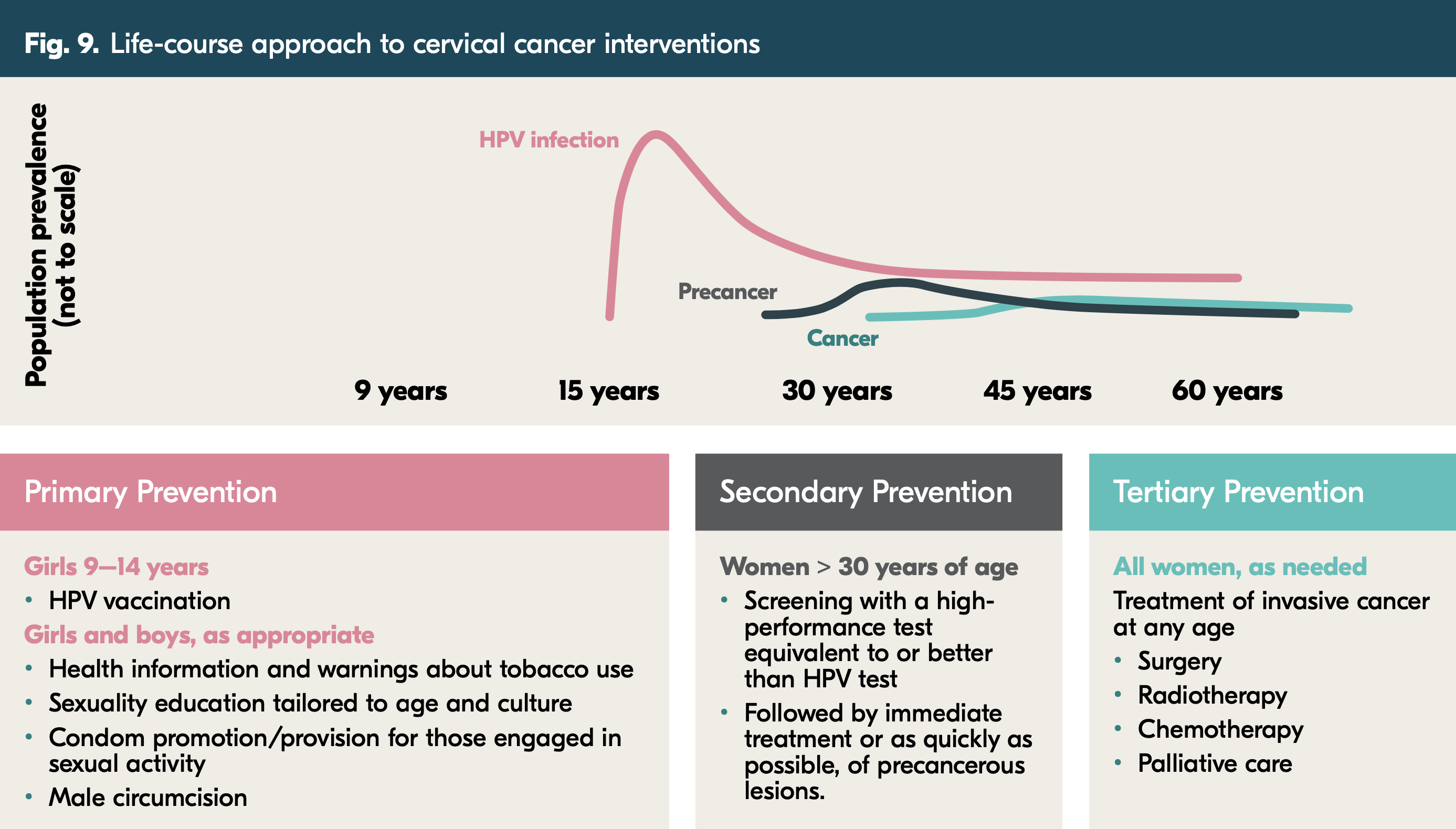

The HPV infections that can later lead to cervical cancer and precancerous lesions begin developing much earlier. A life-course approach to cervical cancer, as outlined in the figure below, has been utilized in several different contexts. It is included in the recommendations from the WHO to eliminate cervical cancer by 2030. Primary prevention begins during childhood and adolescence, with an HPV vaccine in addition to sexual health education and other health services. Secondary prevention includes screenings and immediate treatment for women in their 30s or older. Finally, tertiary prevention aims to treat women of all ages diagnosed with invasive cancer.

Given the global growth of the older adult population projected in the next 30 years, the importance of sexuality to people as they age, and the right that people have to enjoy a rich and healthy sexual life into old age, it is critical that SRH programs consider this population in their intended audiences and outreach strategies. Holistic health care—providing health services and care for the interrelated aspects of people’s lives at specific life stages and as they age—must include sexual and reproductive health care.

Want to learn more? Read about TogetHER for Health and PSI’s work and the importance of cervical cancer integration into broader SRH programs in this Q&A with Heather White, executive director, TogetHER for Health; Eva Lathrop, global medical director, PSI; and Guilhermina Tivir, nurse coordinator, PEER Project, PSI.