Lessons from Ghana to Inform DMPA-SC Safe Storage and Disposal

Providing women with containers for DMPA-subcutaneous (DMPA-SC)* storage and sharps can help to encourage safe self-injection practices at home. Improper disposal in pit latrines or open spaces remains an implementation challenge to safely scaling this popular and highly effective method. With training from health providers and a provided puncture-proof container, self-injection clients enrolled in a pilot study in Ghana were able to appropriately store and dispose of DMPA-SC injectable contraceptives, offering lessons for scale-up.

* Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate administered subcutaneously (DMPA-SC) is an all-in-one injectable contraceptive that is administered every three months.

Increasing access to injectable contraceptives through DMPA-SC self-injection

Global popularity of injectable contraceptives has steadily increased over recent decades, and intramuscular DMPA is the method of choice for many users across sub-Saharan Africa (Tsui et al. 2017). More recently, several countries have introduced a newer injectable, DMPA-SC (brand name Sayana® Press), and its all-in-one Uniject™ device (Figure 1), which provides the option of home self-injection (PATH 2017a, PATH 2017b). The autonomy and privacy made possible with DMPA-SC (Murray et al. 2017) are especially attractive to young people, new family planning (FP) users, those who want to use the method covertly, as well as women who live in rural areas or far from facilities (Nai et al. 2020; Cover et al., 2018; Keith et al. 2014).

While there is widespread interest in improving access to self-injection, implementation science is needed to better understand this new delivery approach, particularly around storage and disposal. The WHO provides recommendations for facility- and community-based use, with some guidance on household-level sharps disposal (PATH & JSI 2019). Existing evidence indicates that without specific guidance, women will likely dispose of DMPA-SC sharps in pit latrines and open spaces, which poses safety and environmental risks (Cover et al. 2016, Cover et al. 2017, PATH & JSI 2019).

Piloting DMPA-SC self-injection in Ghana

To reach its FP2020 goals, Ghana has focused on introducing and scaling DMPA-SC provision in public and private health facilities. To inform national planning efforts, the Ghana Health Service (GHS) prioritized research on home-based self-injection to better understand storage and disposal practices in a context where at-home disposal in pit latrines and open spaces is explicitly not allowed. The Evidence Project, led by the Population Council with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mission in Ghana, collaborated with the GHS to conduct a feasibility and acceptability study introducing DMPA-SC and self-injection.

The DMPA-SC and self-injection introduction process through this study were conducted in rural, peri-urban, and urban areas within two regions of Ghana— Ashanti and Volta. Across these two regions, a cascade training approach was used to train a total of 150 FP providers at eight public health facilities through three-day training workshops on DMPA-SC counseling and administration, including how to teach clients to self-inject correctly. Following the trainings, DMPA-SC was incorporated into comprehensive FP counseling and services at these facilities. Those clients who voluntarily chose DMPA-SC as their contraceptive method were offered the option to be trained by the provider on self-injection. After self-injection instruction and assessment by the provider, the client was then permitted to self-inject under provider supervision and given two doses of DMPA-SC to take home for future self-injections.

Self-injection clients were also given information on DMPA-SC safe storage and disposal, which included instructions to: 1) store the Uniject™ devices in a cool, dry area at room temperature; 2) dispose of them in a puncture-proof container; and 3) return that container to a facility when it was full or when then woman needed a refill of DMPA-SC. In addition, each client was provided a puncture-proof container that could hold up to 5 used Uniject™ devices (Figure 1). To understand women’s experiences with DMPA-SC and self-injection practices, we conducted quantitative interviews with 568 women (18-49 years) following their initial, second and third injections as well as in-depth qualitative interviews with 58 women after their scheduled third injection. A full description of the intervention and study methods can be found at Nai et al. 2020.

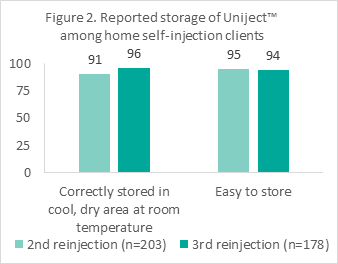

Safe and private home storage of DMPA-SC is feasible and “easy”: Nearly all women reported storing the Uniject™ devices as instructed in a cool, dry area at room temperature (96% after third injection) and found this easy to do (94%). These findings held across age groups, new and previous FP users, and women of all education levels. Women were able to keep DMPA-SC out of reach of children, and they were successful in keeping the devices away from family members for privacy, if desired.

“Once you are done [with the injection], you put it in a container and keep it under the dustbin, no child should have access to it to play with it” – Client 1

“She said I would keep it in the fridge, or I would store in a cool place so that it is not affected by heat for the medication to spoil. I also do not have a fridge so when I came home I have a small pot so I placed it inside…so that the children will not touch it…I placed it at the back of my bed so they can’t reach it.” – Client 2

“I want everything to be secret kept away from my parents, so I stored it [Sayana Press® Press] in my first aid bag and placed it in my trunk and it is always safe there” – Client 3

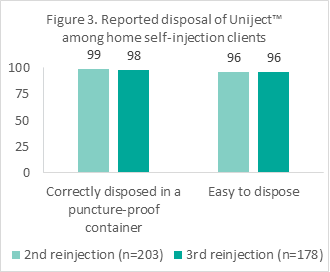

Puncture-proof containers important for safe disposal practices: Almost all the women also reported correctly disposing the devices in a puncture-proof container (98% after 6 months) and found this easy to do (96%). Both younger women and those over age 25 years, new and previous FP users, and women of all education levels correctly disposed of the devices and found this easy to do. However, some disposed of it in the toilet and reported that they were told by providers to do so if they were not given a container. Others who were not provided with a container mentioned being told by providers to keep the used syringes in a tin.

“I put all inside the container after using them and give it to them when they come.” – Client 4

“I disposed of it in the container given to me by the nurse and after I am done with the injection, I returned it back to them to properly dispose it off. That’s what I was told to do so I followed that same procedure and it helped yeah. It made everything secret… I had a problem of taking it back to the clinic because of my time … I am always in the school … [But] the best way is to take it to the clinic back because I want it to be secret so there is no way I have to keep it in any other place.” – Client 3

“I was not given [a container]. I was told the containers were not available at that time, so I was not given… I wrapped it in … old newspaper and put it in … black polythene bag before putting it in the pit latrine” – Client 5

Return of used sharps to health facilities feasible yet challenging: Containers received by women from the health facility could easily hold up to 5 Uniject™ devices; therefore, women were not necessarily expected to bring the container back for disposal during the 6-month study period. Some women reported returning the container (37%) or giving it to community health workers (CHWs) who visited their homes for child check-ups. Some women who took the container back to the facility reported difficulties related to time or transportation costs.

Applying lessons learned for DMPA-SC safe storage and disposal practices to support self-injection

Our study demonstrates that with proper training, women are able to safely store and dispose DMPA-SC. These findings are relevant for other countries that seek to expand access to DMPA-SC through self-injection while addressing safety and ecological hazards associated with disposal of used sharps into pit latrines and open space disposals. In Ghana, study results led the GHS to include containers in nation-wide scale up plans for home self-injection of DMPA-SC.

Emergent promising practices include:

- The provision of DMPA-SC for home self-injection should include containers for safe disposal of used Uniject™ devices.

- Puncture-proof containers provided in this study were discreet and could hold up to five Uniject™ devices.

- If containers are not available, providers should discuss alternatives that do not involve throwing the used devices in a pit latrine or an open space.

- Providers can describe other household containers that women likely already have, such as petroleum jelly containers made of plastic with screw-top lids (Figure 1), that could be used as a safe alternative.

- Increasing options beyond returning filled containers to the health facility can also facilitate proper disposal.

- Alternatives such as pick up by CHWs who are already visiting the household for other reasons, or bringing filled containers to a convenient drop-off point such as a pharmacy or other nearby facility, may avert added transportation time and costs.