The Growing Impact of the Digital Gender Gap

Equity Considerations for Digital Technologies for Family Planning During COVID-19 and Beyond

The race to adapt to COVID-19 has resulted in a shift to virtual formats for health care training and service provision. This has amplified reliance on digital technologies. What does this mean for women seeking services but lacking the knowledge of and access to these technologies?

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of digital solutions in family planning programs, moving many services to digital formats on mobile phones and other devices (often known as mHealth or digital health). Many successful approaches and adaptations will likely become embedded in family planning implementation, data measurement, and monitoring, even when the pandemic’s hold on our day-to-day lives lessens. While these innovations can help sustain program progress (see Applications of the High Impact Practices in Family Planning during COVID-19, 2020: An Adaptation Crash Course, this recording from a session at the International Conference on Family Planning, and A Pandemic within a Pandemic), we cannot forget how these approaches intersect with inequities in global health. The race to adapt to COVID-19, and the resulting shift to virtual formats for health care training and service provision has amplified reliance on digital technologies. What does this mean for women seeking services but lacking access to and knowledge about these technologies? Have we allowed for the digital gender gap to become even more exclusionary? We discussed these questions with a few experts in this field. They shared tips implementers can consider as they adopt digital solutions for family planning in the context of the digital gender gap.

The Digital Gender Gap

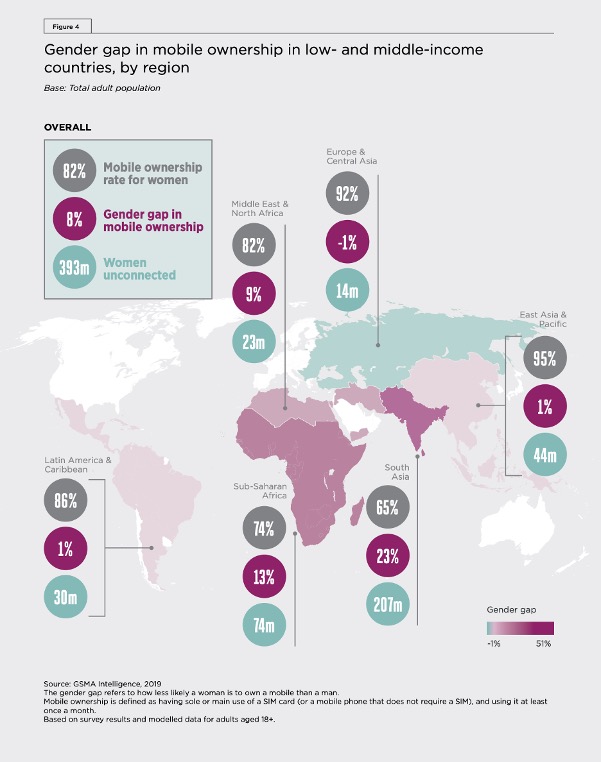

We know a digital gender gap impacts women’s access and ability to use digital technologies, including smartphones, social media, and the internet. This problem also exacerbates existing inequities, including poverty, education, and geographic access. The digital gender gap is worse for women who have lower levels of education, low income, are older, or are living in rural areas. Across low- and middle-income countries, those in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia face the most significant challenges connecting to digital technology. In South Asia, there is 65% mobile phone ownership, with a 23% gender gap in ownership, leaving up to 203 million women unable to access a mobile phone and associated digital services (see the figure below). In addition to gaps in mobile phone ownership, there is also a gap in mobile internet usage. For example, in Bangladesh, there is a 52% gender gap in mobile internet use. This usage gap is 29% in Nigeria and 48% in Uganda (GSMA Mobile Gender Gap Report, 2020).

A variety of potential factors including social norms and affordability, among others, contribute to the digital gender gap. For generations, social norms have designated men as responsible for technological aspects of daily life, relegating many women to non-technological household roles. Social norms that influence whether a woman receives higher education or can maintain employment outside the home also impact digital technology use.

In general, social media may not be the most welcoming space for women due to unchecked harassment in online spaces where gender norms and violence are perpetuated. In India, 58% of women report experiences of online harassment, and 40% reduced their device use or deleted accounts as a result as shared in this Gender & Digital Webinar. A presenter at this webinar, Kerry Scott, associate faculty at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health (JHSPH), reminds us that the cost of maintaining a phone line can be prohibitive. In some cases, women may regularly change their mobile numbers to get cheaper rates, which can lead to disconnection from relevant services and resources.

Relatively lower phone ownership, internet access, and social media presence mean women already have limited options to access and share information as it relates to their health. The problem is only compounded when this barrier intersects with other factors, including:

- Income.

- Geography.

- Education levels.

Limited digital access translated to barriers in accessing family planning information. For example, Onyinye Edeh, founder of the Strong Enough Girls Empowerment Initiative, observes from working in Nigeria that younger girls may be forbidden by their parents from using social media. This causes them to miss out on important information and knowledge related to family planning among other topics.

The digital gender gap further enforces inequity in knowledge management for global health. Digital platforms themselves reflect gender biases: Men are the primary stakeholders in their development and design. Women are not necessarily intended to be the target user. This, when combined with the obstacles to accessing these platforms, can have a snowball effect that perpetuates the gap. The digital gender gap extends across many fields and populations, posing a serious challenge to program designers and implementers.

The Digital Gender Gap and COVID-19: What Does This Mean for Access to Family Planning Information and Services?

While many family planning programs had already adopted digital technology to support some service delivery tasks, such as counseling, follow-up, and referral, this shift accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Are decision-makers considering the gaps in access to and use of digital technologies as this shift continues? The mHealth researchers and practitioners we spoke with warned that programs, policies, and general COVID-19 adaptations can do more to address the digital gender gap. For example, a common adaptation is phone-based hotlines to discuss family planning options with a counselor, but are those hotlines accessible by rural women? By women who don’t have much training on how to use a mobile phone? By women whose husbands control their phone use? These are important questions for us to think about when implementing a digital adaptation.

Digital health innovations will best serve clients and support providers only if steps are taken to ensure equity in implementation. Recognizing how your family planning program can integrate gender-equitable concepts and strategies will help lessen the exclusionary effects of the digital gender gap.

Program Spotlight: Digital Literacy to Dismantle Gender Inequality

The Strong Enough Girls Empowerment Initiative (SEGEI) partners with a non-governmental organization in Nigeria on the “Girl Advocates for Gender Equality” project. Together, they are training 36 adolescent girls across Nigeria to participate in bi-weekly WhatsApp mentorship sessions on topics including:

- Sexual- and gender-based violence.

- Girls’ education, financial literacy.

- Women in leadership.

- Science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM).

The girls use their phones to capture pictures and videos of outreach to other girls outside of the program, creating a cascade of learning in their communities. See some of their posts on Instagram.

Digital Health Amidst a Digital Gender Gap: How to Adapt Effectively

Here are some other short- and long-term changes your program can make to integrate gender considerations with mHealth. (Francesca Alvarez, IGWG; Onyinye Edeh, SSGEI; Erin Portillo, Breakthrough ACTION; and Kerry Scott, JHSPH, contributed to these tips.)

Short-Term Changes to Make/Considerations

- Include a digital literacy component within your intervention before moving services to digital formats. Understand your target group’s level of competency and digital technology access needs.

- Engage men! Think about it: If men are engaging with social media and phone use, family planning programs should target them as both users of family planning and as partners. Erin Portillo cited the comparative lack of digital activities geared towards men’s family planning needs. Given that men are the ones more likely to be online, programs should take advantage of online spaces to send messages about gender-equitable family planning behaviors. Check out this case study from the Digital Health Compendium about a telehealth program in Uganda that connects men to information on modern contraception.

- Think of a mobile phone as a shared device among partners, and play to the strengths of that. This could mean that partners use their phones together to obtain information about family planning or seek services through joint telehealth sessions (Gender & Digital Webinar).

- Call for “safe spaces” online where harassment is not tolerated. Engage local influencers to help convey this concept (Gender & Digital Webinar).

Long-Term Changes to Make/Considerations

- Consider who may be excluded from your digital intervention. It’s likely not just women. Think about other socioeconomic factors, including: education level, rural/urban residence, and age, that may impede access to health. For example, to address Onyinye’s point about youth in family planning, intentionally try to make online spaces more youth-friendly.

- Consider language barriers on mobile platforms. Kerry Scott explained how these become exclusionary, especially for poorer, older women who have never left their communities. A good mHealth program should account for linguistic diversity.

- Collect more sex-disaggregated data. The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) recently added questions about phone use, which is a great starting point to understand potential gender gaps. Design data collection that asks questions related to digital literacy and access, and includes adolescents as well.

- Sensitize healthcare providers to issues related to the digital gender gap. Provide training on digital literacy for family planning providers, including how to speak with clients about using their phones to seek information and services, and how to recognize when barriers prevent their clients from accessing what they need.

- Design interventions that address the root causes of the digital gender gap: The contextual social norms as well as economic and cultural factors. Apply intersectional approaches to address the multiple barriers women from different identities and backgrounds face.

So, has the digital gender gap become even more exclusionary? We would argue that it has. The digital gender gap itself may not have expanded (many women may have more access to digital technologies today than they did five years ago), but the nature of the gap has evolved so that the impact of not having access creates greater disadvantages than before. Now, not having a phone or knowing how to use it could mean that a woman has fewer opportunities to gain information about family planning services in her area, while those who can fully participate in digital spaces can better address their reproductive health needs and goals.

The experts we spoke with reminded us that mHealth is not a “silver bullet.” Digital health, if implemented alongside larger health systems strengthening programs, can be transformative. But the full benefit of this transformation will only come if the digital gender gap is accounted for and steps are taken to mitigate its impact on women’s access to and use of digital health technologies. It should be part of a solution, capitalizing on existing relationships and strengths, not an isolated innovation.

Suggestions for further reading: