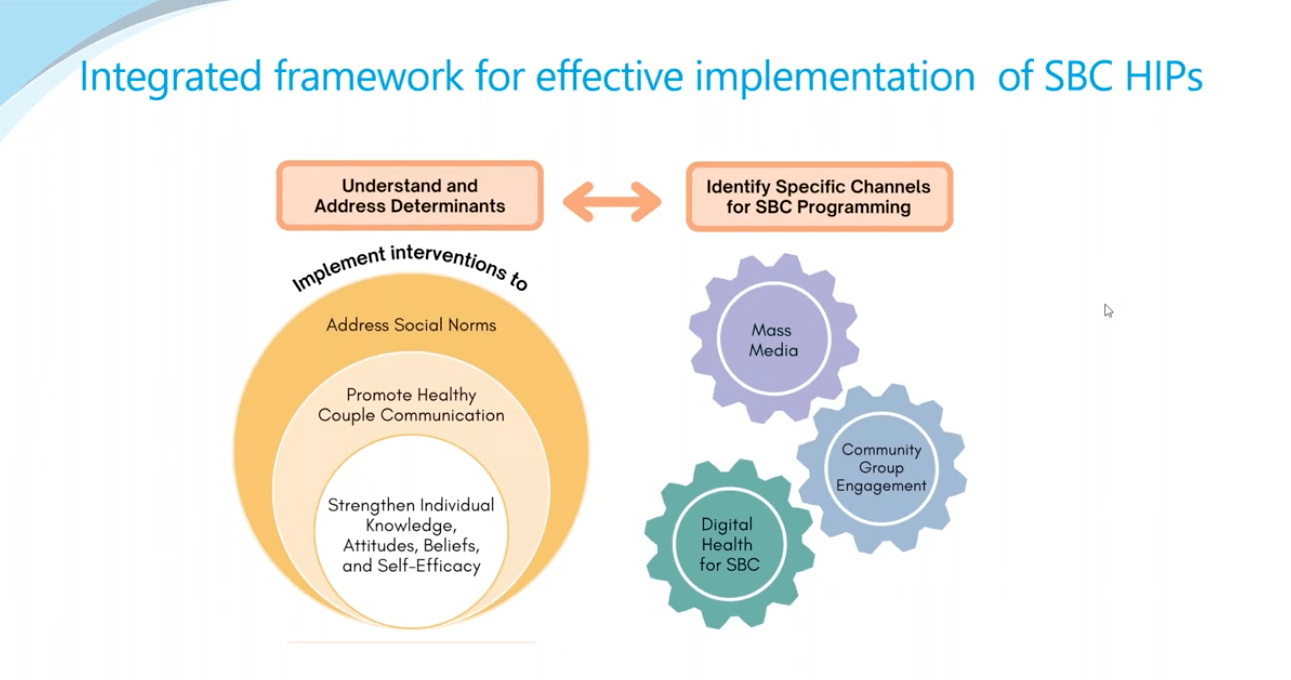

New HIP Briefs on Social and Behavior Change (SBC) for Family Planning

During the SBCC Summit in Marrakech, Morocco in December 2022, The HIPs Partnership hosted an event to launch three new High Impact Practice (HIP) briefs on Social and Behavior Change (SBC) for family planning. Titles and links to the briefs are as follows:

- Promoting healthy couples’ communication to improve reproductive health outcomes

- Knowledge, Beliefs, Attitudes, and Self-efficacy: strengthening an individual’s ability to achieve their reproductive intentions

- Social Norms: Promoting community support for family planning

The December 2022 event featured presentations from the authors of the new briefs—along with experts in these practices. The speakers offered their perspectives and highlighted the importance of the new briefs. The goal of this launch event was to share this new suite of SBC HIP briefs with public health decision makers and SBC practitioners who can use the briefs to advance family planning policies and programs.

Webinar Series on new SBC HIP Briefs

As part of continued dissemination of the new briefs, HIPs partners held a webinar series from March – May 2023 to offer a more in-depth look at the evidence and implementation guidance included in each of the new briefs. Each webinar included an overall introduction to the HIPs, a summary of the SBC HIPs, an overview of each new HIP brief, an implementation perspective, and question and answer (Q&A) session.

Below is a summary of the HIPs introduction, which was the same across all three webinars, followed by brief highlights from each webinar.

HIPs introduction (included in all three webinars)

Each webinar began with a welcome and introductory remarks from Maria Carrasco, Senior Implementation Sciences Technical Advisor, Office of Population and Reproductive Health, USAID. She introduced the webinar and then provided an introduction to the HIPs.

The HIPs are family planning practices that are vetted by experts against specific criteria: replicability, scalability, sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and evidence of impact in achieving certain family planning outcomes. HIP briefs are short and written using clear language. There are four categories of HIP briefs: Enabling Environment Service Delivery, Social and Behavior Change (SBC), and Enhancements. All HIP briefs include a summary of evidence as well as tips for implementation. All briefs can be found on the HIPs website.