Strengthening Emergency Preparedness and Response in Family Planning

Insights from a Recent Learning Circles Cohort in Anglophone Africa

Learning Circles are highly interactive small group-based discussions designed to provide a platform for global health professionals to discuss what works and what doesn’t in pressing health topics. In the most recent cohort in Anglophone Africa, the focus was addressing emergency preparedness and response (EPR) for family planning and sexual and reproductive health (FP/SRH).

Focusing on emergency preparedness and response (EPR) for family planning and sexual and reproductive health (FP/SRH) is crucial to ensuring continuous access to essential health services, building resilient health systems, and developing strategies. This allows for quicker response to safeguard the health and well-being of vulnerable populations, including women, adolescents, and people with disabilities, especially in times of crisis.

Accordingly, emergency preparedness actors are advocating for a more comprehensive framing of emergency preparedness that extends beyond just crisis response. The preferred term by these actors—“resilience”—suggests a continuum of actions across sectors, including health, that include planning for, responding to, and recovering from crises. Therefore, investment in EPR:

- Strengthens existing health systems

- Increases cost-effectiveness, with holistic planning and budgeting for action and mitigation

- Allows for quicker responses

- Helps countries reduce gaps in healthcare and other essential services, including SRH and contraceptive methods

It is necessary to highlight the FP/SRH needs of underserved and overlooked groups, such as people in humanitarian settings and people in situations of vulnerability (for example, adolescents and young people, as well as people with disabilities). It is also important to advocate for more effective and evidence-informed responses and resources.

Through highly interactive, facilitated group discussions, the Learning Circles model offers mid-career FP/RH professionals—including program managers, technical advisors, and policymakers—the opportunity to engage in a series of virtual peer-to-peer learning sessions to generate insights that can help improve their interventions. This Learning Circles cohort aimed at providing practical knowledge regarding EPR programs, strengthening partnerships among implementing partners and creating realistic action plans to address unique challenges faced by participants. The goal was to create a supportive and inclusive environment where everyone could learn and share their knowledge and experiences. The series included five weekly virtual sessions and a WhatsApp group to continue conversations and engagement between the sessions. To kick things off, participants joined the first session to introduce themselves to their fellow peers in the Learning Circle cohort. The participants came from six African countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Sudan) and represented different professional backgrounds ranging from: emergency response professionals; youth SRH advocates; program advisors focusing on social inclusion; gender, advocacy, and integration; climate and environment-focused professionals; agricultural extension workers; climate change experts; and population, health, environment, and development (PHED) practitioners.

Setting the stage: What exists

The second Learning Circles session focused on facilitators and participants discussing the current landscape of EPR in FP/SRH and aligning on a common framework in which to frame their conversations. During the course of this session, the following points were raised:

- Africa has experienced a range of emergencies and disasters ranging from natural phenomena to conflicts and wars. Many countries experiencing these events remain highly vulnerable to future emergencies.

- Efforts focused on reactive measures rather than preventive strategies have led to inadequate coordination across sectors, impeding communities and countries from achieving optimal development outcomes, particularly in public health.

- SRH outcomes (including contraceptive access) have been affected by these crises, along with broader reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health, including nutrition (RMNCAH+N) programs.

Increasingly it has become evident that all countries are susceptible to emergencies and hazardous events as per the fragility index ranking. According to the UN Refugee Agency’s (UNHCR’s) Emergency Handbook, neglecting SRH in emergencies has led to grave consequences including preventable maternal and newborn deaths, sexual violence and subsequent trauma, unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions, and the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

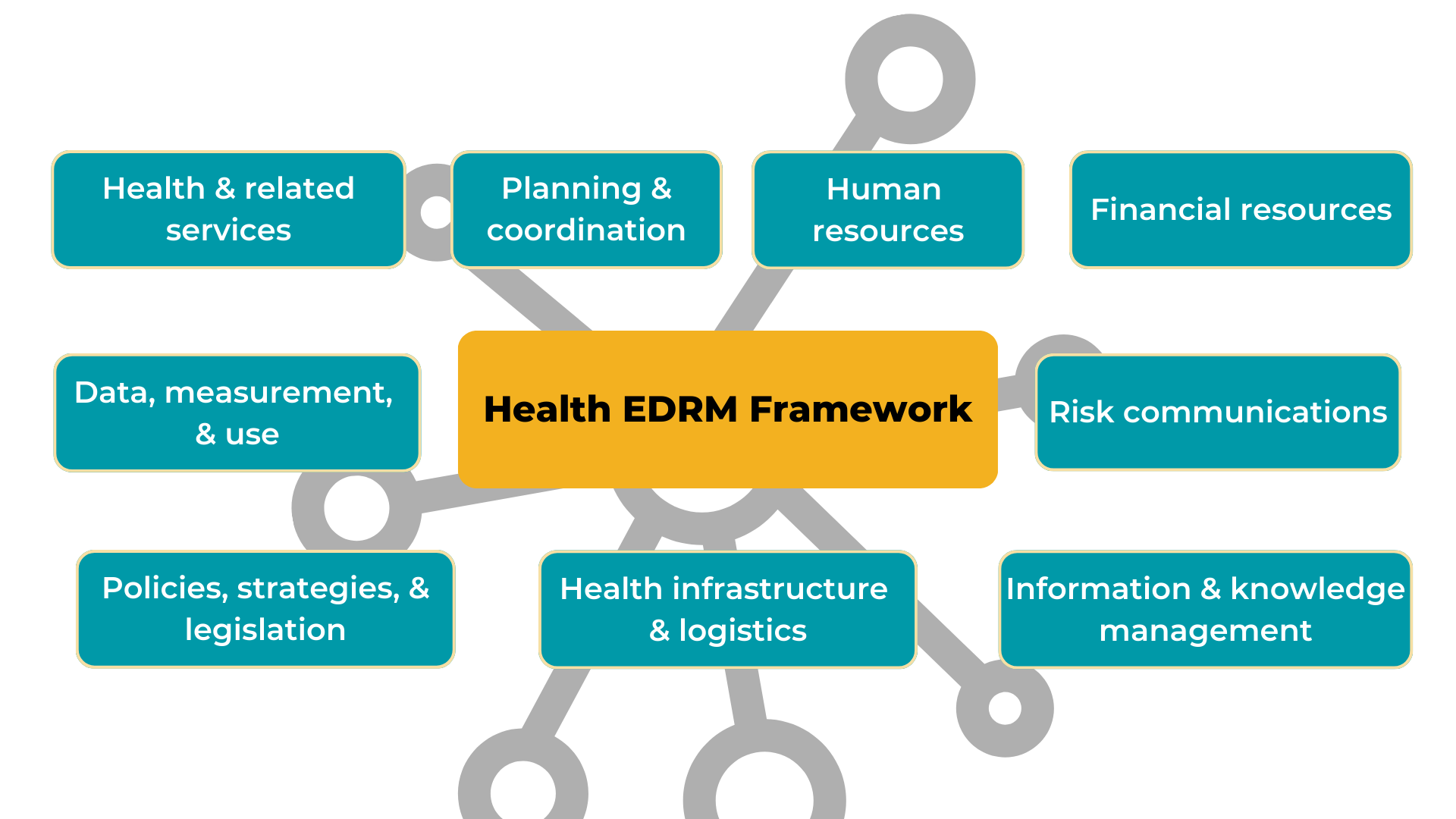

Participants also shared key resources on this topic, such as the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management (EDRM) Framework as a resource to anchor discussions as it is derived from good practices and achievements across related fields such as humanitarian action, multisectoral disaster risk management, and all-hazards EPR. The participants shared some useful resources for addressing EPR within FP/SRH programs, which included the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP), referral tools, workload assessment tool, commodity and supplies quantification tools, and the Sector Wide Approach (SWAp) framework.

Effective practices: What works

During the third session, innovative knowledge management techniques such as Appreciative Inquiry and 1-4-All were employed to reflect on outstanding experiences in EPR for FP/SRH.

The session featured a distinguished guest speaker—an EPR consultant from FP2030—who provided valuable, practical insights into SRH preparedness. The consultant shared key elements and resources essential for improving readiness, including the critical importance of maintaining SRH services during emergencies as life-saving care. This session highlighted how proactive strategies can ensure service continuity in times of crisis.

Participants engaged in breakout group discussions, where they recounted their exceptional EPR experiences, identified factors that contributed to their success, and detailed tools that helped them achieve success (processes, resources, etc.). In the plenary session, they shared commonalities and unique aspects of their success stories, shedding light on practical lessons learned.

The themes and strategies discussed included:

Planning and coordination

- UNHCR brought different sectors together and allocated tasks.

- For preparedness, SWaP and coordination were set-up involving the contribution of key community leaders, state Ministry of Health (MoH) as chair, and implementing partners.

Collaboration

- Used stakeholder mapping tools to facilitate coordination and identify key actors involved.

- Worked closely with MoH to ensure effective service delivery.

- UNHCR and other partners worked together to assess available resources and mobilize them effectively, including essential supplies.

Community engagement

- Through resourceful leaders, participants were able to understand the needs of young women and mothers.

- Communication with the community through an educated scholar and the community healthcare workers, religious leaders, and women of reproductive age. The scholar facilitated the meeting and provided the Quran for reference.

Tools/resources

- Workload assessment tool to assess the workloads of men and women, recognizing that their different responsibilities affect their ability to access services. This helped in tailoring service delivery to meet specific needs based on gender.

- An internally developed tool was used to map the movement patterns of nomadic communities by the International Rescue Committee (IRC).

- Referral forms and patient registers to help track community members once discharged.

- Minimum initial service package (MISP) to help plan in crisis situations.

- Data collection tools to help plan for availability of commodities.

Identifying Gaps: What doesn’t work

“Lack of coordination among stakeholders during emergencies often leaves vulnerable communities without timely FP/SRH services.” – Learning Circles participant

While many countries around the world have made significant progress in addressing EPR in FP/SRH, numerous countries, programs, and individuals still face obstacles to achieving sustainable solutions for these challenges. Participants were asked to reflect on a project they were involved in that did not succeed in EPR for FP/SRH and to identify the factors that contributed to the failure or setback.

To help tackle these challenges, Knowledge SUCCESS employed a knowledge management technique known as “Troika Consulting,” during the fourth session. Participants were asked to identify a specific challenge they were facing and were then organized into small breakout groups of three. Some key challenges raised—and pieces of advice provided—are indicated below.

Partner coordination

- The government should take the lead in the coordination of partners implementing EPR.

- Develop a terms of reference for the FP/SRH monthly coordination meeting with clear roles and responsibilities for the secretariat and technical working group (TWG) members. Provide timely updates to members.

- Ensure that the MoH and the institutions responsible for public health emergency response are members of the FP/SRH TWG.

Inconsistent resource allocation

- Tailor policies around the allocation of resources for the preparation phase and not just response.

- Reserve resources to ensure the availability of SRH services (particularly FP) to avoid reprioritization of key SRH funding for other services.

Cultural barriers

- Involve the most at-risk communities to drive the responses.

- Engage in continuous dialogue with these communities to slowly get a better understanding of the culture and beliefs in our EPR approaches and responses, rather than being prescriptive.

Restrictive policies in addressing AYSRH

- Prioritize data for decision making to help policy makers understand the magnitude of maternal mortality as a result of lack of the essential services.

- Identify champions within the political space to help with advocacy efforts.

Essential commodities and products

- Broker technical assistance with UNFPA to provide supply chain capacity building to MoH staff.

- Engage local leaders to monitor demand levels and provide feedback, ensuring supplies align with actual needs and are prioritized correctly.

- Prepare contingency plans for common barriers such as blocked roads, extreme weather, or fuel shortages, with alternative suppliers or routes.

- Set up small, strategically located distribution hubs closer to end destinations, allowing for shorter last-mile routes.

Commitments and next steps

“I am committed to implementing a community-centered approach to emergency preparedness in my region to ensure no one is left behind.”

During the final session, participants made commitment statements outlining specific action steps they plan to take in the near future. These statements were rooted in realistic and achievable actions that participants can pursue using their available resources.

Participants developed commitment statements to implement immediate, practical actions to strengthen EPR in FP/SRH. They covered a variety of themes and outcomes including:

- Capacity strengthening: One participant committed to engage with five youth-led organizations to strengthen their capacity to integrate EPR into their FP/SRH programs.

- Community engagement and sensitization: One participant committed to conduct an awareness session for 30 young people in the community on the importance of FP/SRH in an emergency setting, focusing on available resources for preparedness.

- Strategies and action plans: One participant committed to ensuring that EPR is clearly highlighted in the ongoing review of an adolescent SRH strategy and the development of the FP communication and advocacy strategy that they are involved in within their country.

- Knowledge exchange and collaboration: One participant committed to being a champion for sharing information on EPR for FP/SRH within the seven districts in which they operate, including with government and non-government actors, during stakeholder engagement meetings over the next year.

Looking Ahead: Recommendations and implications

The Learning Circles participants explored how to apply the lessons learned from successful EPR program implementation to challenges that may be faced in future emergencies. During the final session, participants were asked to imagine this scenario:

By 2034, your country’s FP/SRH emergency preparedness and response system stands as a global exemplar in making climate-resilient health systems successful. Inspired by this achievement, neighboring countries and beyond express a strong desire to learn how your EPR in FP/SRH intervention operates, so they can replicate or adapt it to their own contexts.

In small breakout groups they brainstormed the factors that would have led to this explosive success, what people would be saying, and who would have helped make this a success.

During plenary, the participants shared a summary of the success factors for the future based on the lessons learned. They included:

- Capacity strengthening of health workforce: A skilled and adequately trained health workforce is central to an effective EPR in FP/SRH programming.

- Proactive planning and readiness: Shifting from reactive measures to proactive strategies in emergency preparedness is crucial.

- Stakeholder engagement and multi-sectoral collaboration: Engaging a broad spectrum of stakeholders—including NGOs, government agencies, donor organizations, and private sector partners—is vital for comprehensive planning and resource mobilization.

- Integration of FP/SRH into policies and guidelines: Mainstreaming FP/SRH considerations into national and regional policies and guidelines is essential for informed and coordinated decision-making.

- Political commitment for domestic resource mobilization: High-level political support can lead to increased budget allocations for EPR activities and long-term investments in FP/SRH.

- Strengthened supply chain systems: Robust supply chain structures are critical to maintaining an uninterrupted flow of FP/SRH commodities, even during crises.

- Advocacy for donor investment in climate-related SRH challenges: Advocacy efforts should emphasize the necessity for donors to support interventions that address climate-induced disruptions to FP/SRH services.

- Local financing for preparedness and response: Prioritizing local financing ensures that countries take ownership of their emergency response strategies.

- Strengthened community health workforce: Reinforcing the capacity of community health workers is fundamental for extending health services to the grassroots level.

- Measurement and data-driven decision-making: Implementing data collection and analysis frameworks is essential for informed decision-making.