Improving Contraceptive Use in Young First-time Parents

Highlighting the Achievements of Community Health Workers in India

With India’s adolescent and youth population on the rise, the country’s government has sought to address this group’s unique challenges. India’s Ministry of Health & Family Welfare created the Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) program to respond to the critical need for adolescent reproductive and sexual health services. Focusing on contraceptive use in young first-time parents, the program employed several strategies to strengthen the health system to respond to adolescent health needs. This required a trusted resource within the health system who could approach this cohort. Community frontline health workers emerged as the natural choice.

List of Abbreviations

| ASHA | Accredited Social Health Activists | NCDs | Non-communicable diseases |

| AYSRH | Adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health |

ORC | Outreach camps |

| ARSH | Adolescent reproductive and sexual health | PSI | Population Services International |

| ARS | Adolescent responsive services | PHCs | Primary health centers |

| AHD | Adolescent Health Days | RKSK | Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram |

| ANM | Auxiliary nurse midwives | RCH-II | Reproductive and child health program |

| ESB | Ensuring Spacing at Birth scheme | SRH | Sexual and reproductive health |

| FTP | First-time parent | TCIHC | The Challenge Initiative for Healthy Cities |

| FDS | Fixed-Day Static | UHIR | Urban health index register |

| HMIS | Health Management Information Surveys | UHND | Urban health and nutrition days |

| mCPR | Modern contraceptive prevalence rate | UPHCs | Urban primary health centers |

| NFHS | National Family Health Survey |

Worldwide, the adolescent and youth population is on the rise. Matching this global trend, India currently has over 358 million young people who are 10–24 years old. Of these, 243 million are aged 10–19, accounting for 21.2% of the country’s population.

As in much of the world, the needs of India’s young people vary substantially by intersecting societal factors such as:

- Age

- Sex

- Stage of development

- Life circumstances

- Socio-economic status

- Marital status

- Class

- Region

- Cultural context

Many of them are out of school or work and in vulnerable conditions. They are likely to be sexually active and are exposed to several health risks such as injuries, violence, alcohol and tobacco use, and early pregnancy and childbirth.

Many of them have limited access to accurate information and services. They face several challenges due to structural inequalities, including:

- Poverty

- Unsupportive social norms

- Inadequate education

- Social discrimination

- Child marriage

- Early childbearing for adolescent girls

These challenges are even more acute for adolescents residing in low-income urban settings.

Responding to this critical need, India’s Ministry of Health & Family Welfare included adolescent reproductive and sexual health (ARSH) as a key technical strategy under its Reproductive and Child Health (RCH-II) program. In 2014, the ministry launched a new adolescent health program, Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK), that underscores the need for strengthening the health system to respond to adolescent health and development needs.

RKSK identifies six strategic priorities for adolescents:

- Nutrition

- Sexual and reproductive health (SRH)

- Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

- Substance misuse

- Injuries and violence (including gender-based violence)

- Mental health

Why Focus on Young First-Time Parents?

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS 4, 2015–16) shows that the age group with the lowest contraceptive prevalence rate are married women 15–24 years of age—more specifically, young, married first-time parents. The survey provides a growing body of evidence for program implementers like Population Services International (PSI) and other stakeholders. The demand for contraceptives among young, currently married women is moderate, around 50%. Only around a third of this demand is met through modern contraceptives. This is perhaps due to India’s social norms, which expect young women to start a family as soon as they are married. According to NFHS 4, only 21% of sexually active women 15–24 in India have ever used any modern contraceptives.

NFHS 4 revealed that Uttar Pradesh, a state in northern India, had a high unmet need for a birth-spacing method among married women between the ages of 15–19 (20.4%) and 20–24 (19.1%). With over 200 million inhabitants, Uttar Pradesh is the most populated state in India and the most populous country subdivision in the world. The evidence showed that health outcomes for mothers and babies were significantly better if they waited two years between pregnancies. Yet, inequitable gender and cultural norms around fertility and provider bias lead many young married mothers in Uttar Pradesh (and elsewhere) to have closely spaced pregnancies that compromise their health.

This age group (15–24 years) faces a unique set of challenges different from those faced by older married women with regards to accessing and using family planning services. The problems these women face include:

- They have limited agency to negotiate contraceptive choices and decisions with their husband and family members. Additionally, spousal communication on FP is extremely poor.

- They are expected to follow the social norms of the Uttar Pradesh community, which includes bearing children as soon as they are married.

- Family planning is not introduced to women who have not yet given birth, especially young adolescent (15–19-year-old) married women.

- They are burdened with household chores and are not allowed to intermingle with the older women in their communities and ASHA/community health workers.

Key Program Design Features

In 2017, The Challenge Initiative for Healthy Cities (TCIHC) started providing coaching support to local governments in Uttar Pradesh to implement evidence-based family planning programs. Of these, five cities (Allahabad, Firozabad, Gorakhpur, Varanasi, and Saharanpur) were selected to add adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health (AYSRH) and contraceptive use in young first-time parents (FTP) to the existing FP program in September 2018. TCIHC based its desk review of RKSK guidelines and strategies identified that RKSK has a cascade approach to introduce adolescent and youth strategies. This meant their strategies of introducing Adolescent Health Days (AHD) at primary health centers (PHCs) or community AHD were being implemented in rural areas. After rural areas were reached, RKSK planned to introduce these strategies to urban areas. The introduction of these strategies to low-income urban segments was, therefore, one of the last priorities.

TCIHC advocated with RKSK and presented a coaching-mentoring strategy. Coupled with demonstrating results on the benefits of rolling out adolescent and youth interventions (with an emphasis on contraceptive use in young first-time parents) in urban pockets in five cities of Uttar Pradesh, their strategy (click to expand):

Advocated for making data on first-time parents more visible

The project amplified the absence of first-time parent data from Health Management Information Surveys (HMIS), existing project health information systems, and available population-level studies. It called for attention to this group at state- and national-level family planning monitoring meetings and with local city health governance teams. The project emphasized making FTP a priority by making its data visible in review meetings.

Conducted Values Clarification Exercises Throughout Health Centers

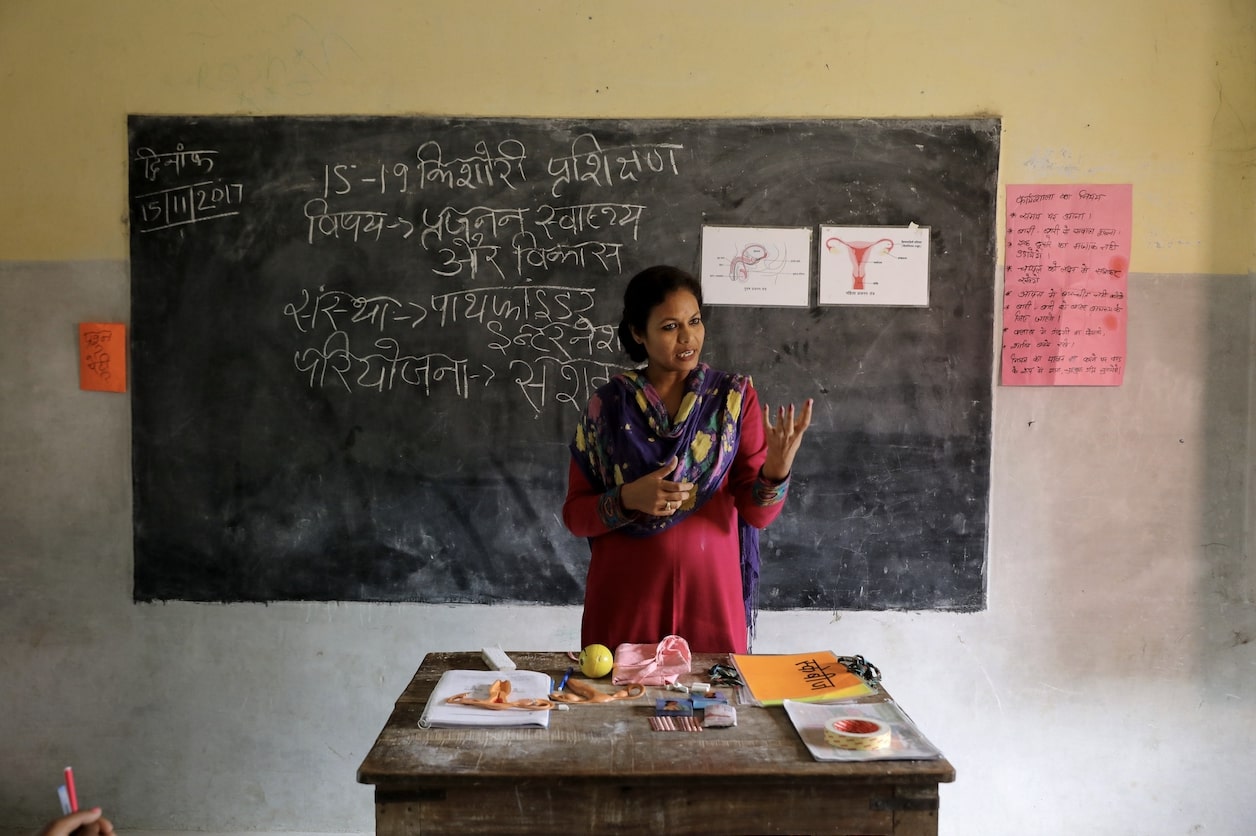

Urban Primary Health Centers (UPHCs) are nested within complex social and cultural settings. Health service providers, as members in these contexts, maintain their own beliefs and value systems. Furthermore, health care systems can influence provider actions in the form of policies and norms. These influences induce provider biases, which may lead to low quality of care, especially for married adolescents or young married couples. TCIHC realized this need and coached RKSK to roll out a whole site orientation of all staff in a UPHC on biased attitudes and beliefs towards youth that they may carry. Working with the system, focal persons of UPHCs—the Medical Officer In-Charge—were developed as master trainers for conducting these whole-site orientations of facility staff on providing adolescent-friendly health services. This values-clarification exercise is critical to improving the knowledge and attitudes of health facility staff to provide non-judgmental, supportive care to adolescents and youth regardless of their age, gender, and marital status.

Urban Primary Health Centers (UPHCs) are nested within complex social and cultural settings. Health service providers, as members in these contexts, maintain their own beliefs and value systems. Furthermore, health care systems can influence provider actions in the form of policies and norms. These influences induce provider biases, which may lead to low quality of care, especially for married adolescents or young married couples. TCIHC realized this need and coached RKSK to roll out a whole site orientation of all staff in a UPHC on biased attitudes and beliefs towards youth that they may carry. Working with the system, focal persons of UPHCs—the Medical Officer In-Charge—were developed as master trainers for conducting these whole-site orientations of facility staff on providing adolescent-friendly health services. This values-clarification exercise is critical to improving the knowledge and attitudes of health facility staff to provide non-judgmental, supportive care to adolescents and youth regardless of their age, gender, and marital status.

Identified the Key Influencer

To demonstrate success, the project identified a two-part goal:

- To reach 100% of first-time parents in the community who are non-users of modern contraceptive methods with information on family planning methods.

- Connecting them to FP services.

This meant that each first-time parent in the community was met and provided correct information on family planning methods and referred to facilities where FP methods are available. This required a trusted resource within the health system who could approach this cohort. Community frontline health worker Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) emerged as the first and natural choice, and were, hence, identified as the “influencer.”

Coached the Influencer

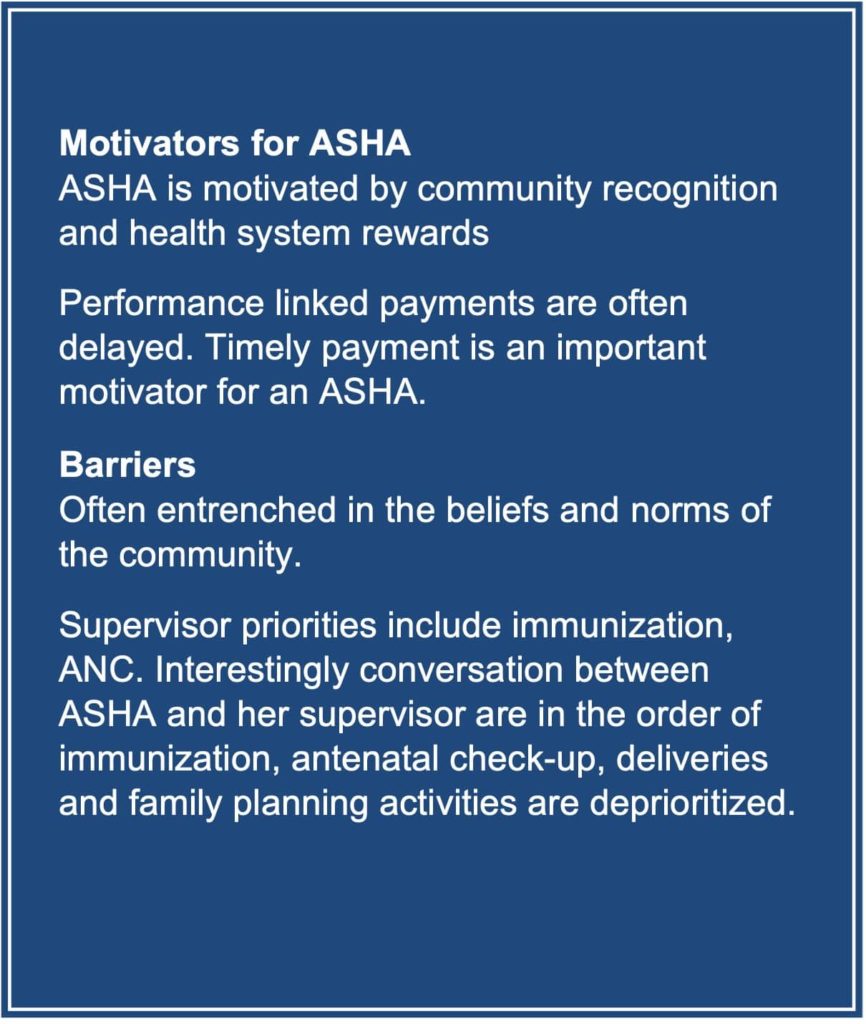

For an ASHA to be the “agent of change” required a behavior change in the ASHA so that family planning and FTP became the priority. Behavior change always requires motivation and the elimination of barriers that prevent a particular behavior from happening and/or encourages another behavior in its place. TCIHC carried out a small exercise with selected ASHAs and identified the factors that motivate and demotivate an ASHA.

Based on these factors, TCIHC adapted its coaching model to build capabilities in ASHAs. They could then achieve the goal of reaching 100% of first-time parents who are non-users of modern contraceptive methods. This required them to understand the data on FTPs to capture various registers and decipher it meaningfully to arrive at programmatic decisions. TCIHC introduced a “data for decision making” three-step coaching to ASHAs through ASHA supervisors, auxiliary nurse midwives (ANM):

STEP 1: Compile all the listed information about families in the community in the urban health index register (UHIR).

STEP 2: Color-code first-time parents from the UHIR register, mark users (and their choice of method) and non-users.

STEP 3: Prioritize home visits to non-users in daily work plan, route map. Segment users for follow-up visits and reminder service.

The project introduced a five-session smart coaching tactic. Under this, ASHAs in a particular city were divided into groups and each group had a diverse group of ASHAs, with some performers, early adopters (some with a growth mindset), and naysayers. This peer exchange enabled quick learning by ASHAs. Slowly this tactic was integrated into the monthly review meetings of the ASHA and her supervisor, an Auxiliary Nurse Midwife.

Gauged Influencer’s Performance

This entire strategy is dependent on the influencer, i.e., ASHAs. To make it most viable, it is important to regularly monitor their performance concerning their work with FTPs. However, a point of consideration is that HMIS in India does not disaggregate users of family planning by age and number of births. In simple terms, age and number of children are not recorded in HMIS, and therefore, it is difficult to ascertain the priority list of clients who may need family planning.

“Learning how to properly fill my diary has helped me to maintain a client record in a systematic manner, and now I can easily and quickly extract specific information like first-time parent and adolescent couple details for family planning.”

Therefore, the program invested in designing a project health information management system (PMIS). The PMIS captured two critical data points: recording the number of women reached with information on FP and recording the number of users of family planning by age, method choice, and parity.

Once the project started gathering this information, it was possible to monitor the following indicators:

- Reach to FTPs

- Update of services at UPHC

- Contraceptive uptake by FTP in each of the facilities

Created Access to Incentives and Recognition

It is important that an ASHA feels motivated to work in FP and with first-time parents. Hence it is important to coach ASHAs on government schemes related to FP, such as the Ensuring Spacing at Birth scheme (ESB). It lays out attractive outcome-based remuneration to frontline health workers for encouraging the adoption of spacing methods. Under this scheme*, ASHAs are reimbursed a little over $6 for their services in counseling women to delay first childbirth and a two-year spacing between subsequent births. The ESB reimbursement is processed only when the woman adopts a method and continues with a method for two years.

It is important that an ASHA feels motivated to work in FP and with first-time parents. Hence it is important to coach ASHAs on government schemes related to FP, such as the Ensuring Spacing at Birth scheme (ESB). It lays out attractive outcome-based remuneration to frontline health workers for encouraging the adoption of spacing methods. Under this scheme*, ASHAs are reimbursed a little over $6 for their services in counseling women to delay first childbirth and a two-year spacing between subsequent births. The ESB reimbursement is processed only when the woman adopts a method and continues with a method for two years.

This scheme had remained underutilized in urban locations. ASHAs were mostly unaware of this scheme and the required paperwork for claims. With no claims being processed, the know-how in processing this claim was missing among the city governance teams.

The TCIHC team advocates, in close coordination with the government, developed simple, easy-to-understand steps for submitting claims. The steps were distributed via handouts and integrated into a coaching session between ASHAs and their supervisors. Additionally, the team coached city governance staff responsible for claiming reimbursement on the required paperwork for the ESB scheme.

*Editor’s note: Programs seeking to implement a similar scheme should verify requirements. USAID’s family planning programs are guided by the principles of voluntarism and informed choice. Information on these principles can be found on the USAID website.

Outcomes

The TCIHC experience from five cities revealed that ASHAs can prioritize young and low-parity women, specifically first-time parents, for family planning by:

- Receiving coaching and mentorship.

- Periodically updating the UHIR.

- Segmenting and listing women based on age and parity.

This practice also aids in the maintenance of a registry of young married FTPs aged 15–24 years and prioritizes the category for household visits. The coaching enables them to easily identify FTPs with unmet FP needs and counsel them to access FP services using a Fixed-Day Static (FDS)/Antral diwas (“spacing day”) approach. Under this, UPHCs provide assured, quality family planning services, including long-acting spacing methods, on widely publicized fixed days and at times known to the community.

Some notable outcomes are (click to expand):

Saturation of FTPs

Of all the women met during the peak intervention period of October 2018–June 2019, almost two-thirds of women were first-time parents. By July 2019, most ASHAs had reached more than 90% of FTPs in their communities with information on FP.

Program Exposure in Last Six Months (Women 15–24 Years in AYSRH Cities)

TCIHC conducted a population-level study, called the Output-Tracking Survey in five AYSRH cities. The survey revealed that almost 67% of women aged 15–24 years with one child reported program exposure. This means they had either been counseled by an ASHA, attended a group meeting on family planning choices, and/or visited one of the three service delivery platforms:

- Urban primary health centers.

- Outreach camps (ORC).

- Urban health and nutrition days (UHND).

Use of Modern Contraceptive Methods (Women Aged 15–24 in Five AY Cities)

The survey results indicated a 17% increase in modern contraceptive prevalence rate (mCPR) among young 15–24-year-old women with one child. The mCPR increased by 9% among all 15–24-year-olds. This unprecedented increase in mCPR and the significant exposure to program activities among this population all point to the role played by the ASHAs in getting FP information and services to young mothers.

What others can learn from our work

- TCIHC approach is an example for other cities to effectively make FTP data visible to the government. It is evident that FTPs need to be reached, and it requires an influencer to reach them in certain contexts.

- Building the capacity of ASHAs to decipher data for decision-making is key to reaching FTPs.

- Involving local government, especially the adolescent and youth chapter, or RKSK functionaries in the case of TCIHC, from the beginning created ownership of AYSRH interventions.

- Coaching the city governance staff, facility-in-charge, and community health workers on existing health systems, schemes, and policies (such as the ESB scheme) through hands-on coaching is a comprehensive way to ensure young first-time parents’ needs are met.

- Establishing Auxiliary Nurse Midwives as ASHA coaches on completing UHIR, devising priority lists of FTPs, and helping them plan their household journeys can support ASHAs in their outreach.

- Recognizing the role of community health workers (ASHAs in India) is important for job motivation—governments should consider this when designing programs. It is important to motivate the influencer. Hence, the city should reward and recognize them from time to time.

- The demand for services at UPHCs generated by ASHA outreach motivates the provider to overlook their personal biases. An interesting narration by Dr. Arshiya Sherwani, MOIC of UPHC Nagla Tikona, details what she felt after being trained on the values-clarification exercise.

Adolescent Responsive Services: Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Furthermore, implementing programs using adolescent responsive services (ARS)—an approach to adolescent and youth services that integrates them into the health system in a systemic way—face several challenges in India. Such challenges impact the quality of SRH services for young people of all genders, including first-time parents. These challenges include:

- Provider biases on offering methods such as injectable to young women is a big challenge.

- Paperwork for reimbursement through the ESB Scheme (ESB), meant to incentivize frontline health workers for encouraging adoption of spacing methods is a complicated process. Knowledge gaps exist in both community health workers/ASHA on how to submit the claims and among the government officers on how to submit the claims and officers on the mechanism to process it. This can lead to delays on both ends.

PSI addressed these challenges through the TCIHC project by:

- Devising a values-clarification exercise where PSI coached the providers to carry out values-clarification exercises as part of the whole-site orientation exercise. This has clarified the biases and myths of many providers.

- PSI has created a simplified leaflet on the ESB scheme that explains how working for FP is a long-term investment in community health workers. In addition, PSI has coached ASHA supervisors, medical officers-in-charge, and city government staff on the process of leveraging the ESB scheme.

The Future of AYSRH in India

Investments in adolescents and contraceptive use in young first-time parents respond to their specific needs in a non-judgmental manner. Overall, adolescents tend to shy away from accessing health services. From studies, we know around 26% of adolescents are less likely to visit public health facilities or camps as compared to women of older age groups. Adolescents tend to access private-sector spaces (such as pharmacies), where short-term family planning methods (pills and condoms) are easily available over the counter, especially in urban areas. Young people need broader choices for FP, the private sector plays a crucial role in this context. Further, city health functionaries need to focus on integrating AYSRH needs into their routine agendas, so programs and initiatives are leveraged and optimally utilized.

Learn more about adolescent and youth reproductive health by catching up on the Connecting Conversations series, hosted by Family Planning 2020 and Knowledge SUCCESS.