Beyond Biology: Integrating Menstrual Health into Sexual and Reproductive Health Programs

Menstrual Health (MH) is a key component of Adolescent and Youth Sexual and Reproductive Health (AYSRH). Many have now recognized menstruation as a human rights issue, since neglecting this area can mean depriving menstruating youth of opportunities to fully enjoy their rights to education, employment, and health. In order to make progress on the UN’s Youth 2030 Agenda—which centers on empowering youth via strategic priorities like supporting relevant education and health services access—we must take an approach to AYSRH programming that proactively and meaningfully addresses MH needs.

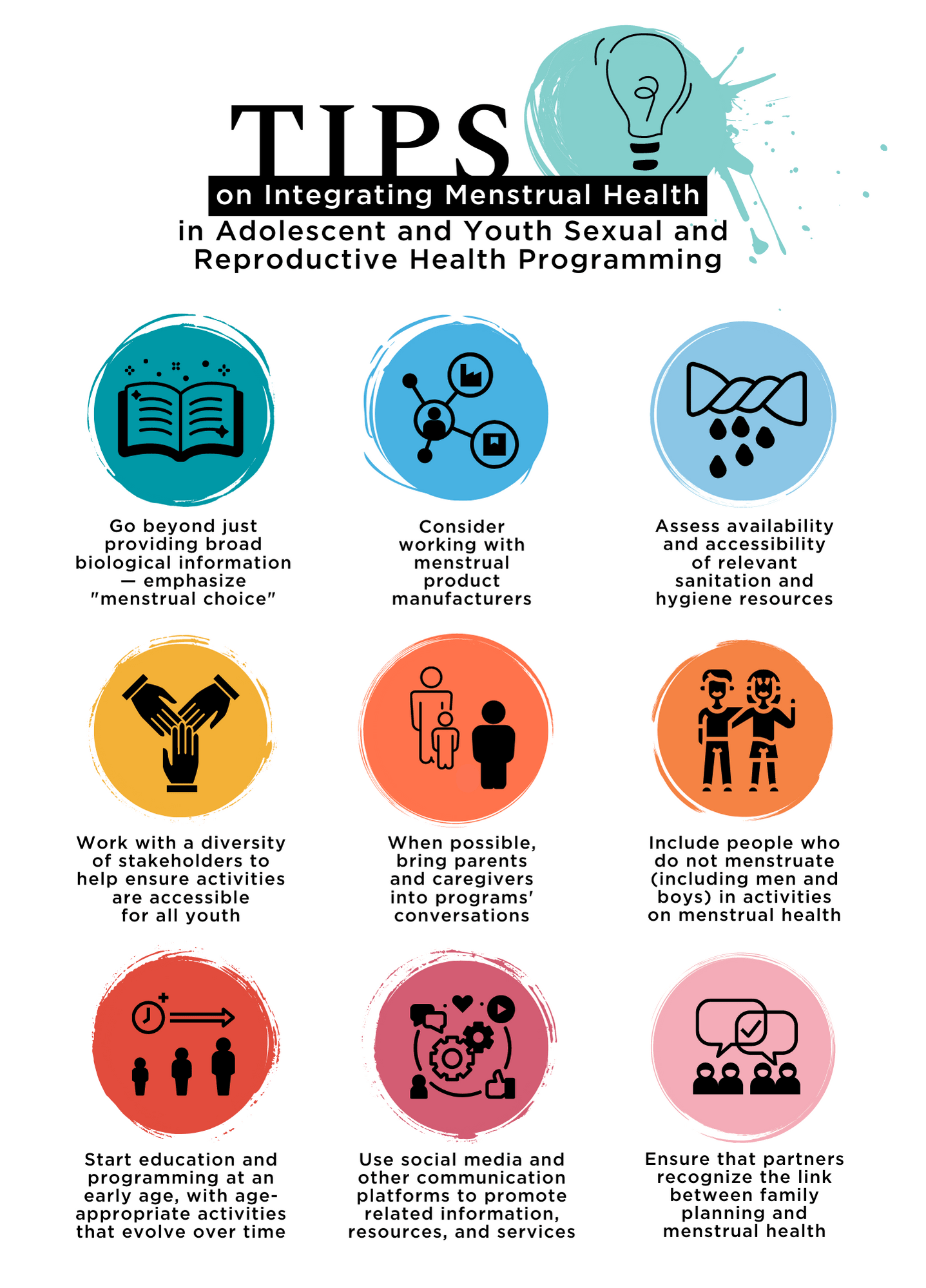

This post will highlight nine recommendations presented by UNFPA’s recent “Technical Brief on the Integration of Menstrual Health into Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights Policies and Programmes” that are immediately doable, use tools that many AYSRH initiatives already have at their disposal, and are particularly relevant to adolescents and youth.

Emphasize Menstrual Choice

Fundamentally, menstruation is a biological process, and it is indeed important to inform people of the biological facts of the menstrual cycle. But it doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Educational materials and relevant programming must also take social, cultural, and financial factors into account. The common misconception that menstruation is a physical or emotional hindrance that inherently limits menstruators’ abilities to participate in public life, leadership roles, and other opportunities is important to understand. The myth that the start of menstruation signifies readiness for sex, marriage, or childbirth is another especially notable —and harmful—misconception affecting young people and their engagement with reproductive health, as well as their risk for gender-based violence and unwanted pregnancy., Program planners must understand and be prepared to tackle these issues.

“Menstrual choice” is a “comprehensive term intended to reflect the importance of ensuring that menstruators are empowered and able to choose how, when, and where to manage their menses safely and effectively.” Placing an emphasis on choice ties into other areas where adolescents and youth should also be enabled to make informed, autonomous decisions regarding their own bodies, like navigating consent in relationships or choosing between different family planning (FP) methods in consideration of future life goals by understanding the potential menstrual “side benefits” or effects of different methods.

UNFPA recommends a positive framework that celebrates menstruation and puberty as reaching growth milestones, challenges stigma and harmful misconceptions, dispels myths surrounding “normal” menstruation, and encourages dialogue and sharing on the topic.

Consider working with menstrual product manufacturers

For those working with adolescents and youth, the UNFPA recommends pairing the distribution of menstrual products with the delivery of accurate information on menstrual health and AYSRH overall.

A variety of different program partners currently support the distribution of free or subsidized menstrual products during awareness-raising opportunities. Prior successes of free/subsidized distribution programs can make for powerful talking points in pursuing partnerships. Note that collaborating with quality local manufacturers in particular can help reduce transportation costs throughout the entire system.

In humanitarian settings, disseminating vouchers or cash transfers for menstrual supplies purchasing might be preferable. Vending machines and similar pickup points can be more accessible to menstruators who are not looking to stock up on products all at once.

Assess availability and accessibility of relevant sanitation and hygiene resources

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) facilities like school and community bathrooms must be readily accessible to all, including those with disabilities, and able to meet the needs of menstruators so that they can wash, dry, and/or dispose of menstrual supplies. There should also be separate and private toilets and private stations for washing reusable supplies.

Ensure young people can directly weigh in on what they need and what improvements can be made to surrounding infrastructure.

Read this ”Checklist on Design Features for Inclusive Sanitation Facilities” for a more comprehensive look at what considerations can be made to improve WASH facilities for menstruators.

Menstruating youth should be able to safely access:

- Clean material to absorb or collect menstrual blood; the products must be acceptable to those who need them

- Physical spaces where menstrual products can be privately cleaned, changed, and/or disposed of, as well as spaces where menstruating people can safely and privately wash themselves

- Accurate information regarding the menstrual cycle, managing menstruation without discomfort or fear, tackling discriminatory perceptions related to menstruation, and any irregularities or signs of menstruation-related disorders—as well as an understanding of how contraceptive use, childbirth, miscarriage, and other pregnancy complications can cause irregularities

- Relevant healthcare resources, including resources addressing pain management and related disorders

Work with diverse stakeholders to help ensure activities are accessible for all youth

Young people of vulnerable social groups experience additional barriers to accessing relevant MH resources and fulfilling their needs. For example, MH initiatives have historically ignored youth with disabilities. Service providers, program staff, and educators must be prepared (with appropriate training and equipment) to support different populations.

Educational campaigns, product packaging, and other communication materials should use inclusive language and account for different communication needs.

Out-of-school adolescents may be especially vulnerable to experiencing menstrual choice limitations and must also be supported in these regards. The UNFPA guidance suggests expanding community-based, out-of-facility delivery methods like mobile and household outreach.

Check out this webinar recap, “One Size Does Not Fit All: Reproductive Health Services Within the Greater Health System Must Respond to Young People’s Diverse Needs,” for tools and guidance on making AYSRH initiatives more inclusive and equitable.

Quick Links to More Detailed Resources

- Guidelines for Providing Rights-Based and Gender-Responsive Services to Address Gender-Based Violence and Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for Women and Young Persons with Disabilities

- Guidance on Menstrual Health and Hygiene (MHH) Section 4: MHH for girls and women in vulnerable situations

- Toolkit for Integrating Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) Into Humanitarian Response

When possible, bring parents and caregivers into conversations

When appropriate and logistically feasible, engage parents, caregivers, family members, and other influential adults in MH-related programming. The Oky period tracker app, for example, was designed to connect young people with relevant MH information, but it also hosts content specifically for parents, teachers, and other community members. Efforts to engage adults should provide practical guidance on open communication with young people, navigating MH-related conversations, and addressing negative gender and social norms to reduce stigma.

Include people who do not menstruate (including ) in activities on menstrual health

Context-tailored initiatives providing accurate, rights-based and gender-transformative MH-related education to people who do not menstruate can be vital to reducing menstruation-related stigma and harassment, as well as improving sexual and reproductive health outcomes overall. In schools, ensuring that MH is promoted can diminish discrimination from boys and male teachers and generally improve educational outcomes for those who menstruate.

Start education and programming at an early age

Very young adolescents (10- to 14-year-olds) are especially susceptible to being overlooked in MH-related programming, even though they comprise a significant portion of menstruators. The UNFPA guidance suggests taking a “life course approach” to promoting MH. That means acknowledging that experiences and behaviors happening to young people early in life will impact their future health outcomes. People at different points in life will need age-appropriate information and resources; comprehensive sexuality education programs often feature menstrual-related topics as a means to further understand issues related to sexual and reproductive health, such as pregnancy prevention.

Use social media and other communication platforms to promote related information, resources, and services

Digital platforms are a useful place to engage with youth and connect them to relevant programs and physical services. There is also great value in creating and promoting one-way, private, remotely accessible “edutainment”-type media content that emphasizes self-care and self-reassurance in celebrating menstrual choice. That said, materials should still indicate when someone might want to seek external, professional support in tackling an MH-related issue.

Social media accounts dedicated to AYSRH will often open the floor to followers’ questions on MH: PSI Angola, for example, runs an educational account where a midwife will answer questions once a week, covering topics that are pertinent to the real audience members “calling in,” like whether or not it is “dangerous” to have sex while menstruating.

Learn more about digital content creation by reading ”Youth-centred digital health interventions: a framework for planning, developing and implementing solutions with and for young people,” a WHO guide on developing impactful digital health interventions.

Ensure that partners recognize the link between family planning and menstrual health

Examples of important intersections between MH and FPg:

- Denial of services, including contraceptive services, to clients due to uncertainty of their pregnancy status can be addressed by applying tools like the pregnancy checklist and low-cost pregnancy tests

- Fertility awareness-based methods (FABMs) and the lactational amenorrhea method (LAM), which are contraceptive methods enhanced by an environment of open communication and familiarity with the concepts of menstruation and fertility, can increase a young person’s understanding of menstruation

- The “NORMAL” mnemonic can be promoted as a way to understand bleeding changes associated with various contraceptive methods (Contraceptive-Induced Menstrual Changes, or CIMCs) and potential lifestyle implications

- Forecasted changes to menses can lead to reluctance with engaging in and adhering to contraceptive methods; these concerns should be accounted for in related communications and resources

MH intersects with family planning in significant ways that should be understood by menstruators themselves as well as the people who support their health. We must ensure that all reproductive health and contraceptive counseling includes comprehensive discussion of the menstrual cycle and contraception-induced menstrual changes.