Entry points

During all stages of reproductive life, men play an important role in conversations and decisions about contraceptive use, family size, and spacing of children. Yet, even with this decision-making role, they are often left out of family planning and contraceptive programming, outreach, and education efforts. We often hear about “engaging men” in the family planning community, but how can we do this effectively? What specific needs do they have that aren’t currently being met?

To address this challenge in eastern Uganda, IntraHealth International, in partnership with ideas42, implemented the Scale-Up and Capacity Building in Behavioral Science to Improve the Uptake of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Services (SupCap) project funded by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Approach

The project used behavioral science to design, test, and scale an intervention that helps increase postpartum contraceptive uptake, improve communication about family planning between couples, and boost knowledge about modern contraceptive methods. The project specifically focused on men due to identified behavioral barriers to postpartum contraceptive use and the lack of dedicated family planning programming for men.

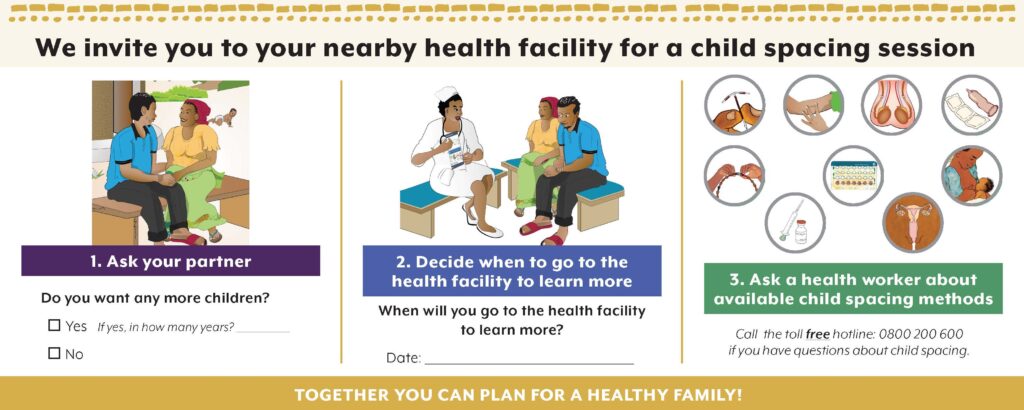

The intervention includes two components, an interactive game called Together We Decide (Figure 1) and a child spacing planning card (Figure 2). The game is played in the community by male partners of postpartum women and is facilitated by all-male village health teams. Through the game, men learn more about different contraceptive methods, discuss short-and long-term financial implications of children, and dispel myths and misconceptions about contraceptive methods. After they finish playing the game, men receive the child spacing planning card to bring home to their partners and discuss a plan to visit a health facility for more information about child spacing methods.

Test phase

The team conducted a quasi-experimental study to test the intervention in six districts of eastern Uganda and found evidence it led to significant improvements in knowledge and attitudes about modern contraceptive methods and joint decision-making. Men in the intervention group were more likely to say that modern methods are a good choice to space children and less likely to say they were the sole decision-maker for contraceptive use in their household compared to men in the control group. Contraceptive use also increased among men in the intervention group. Based on these results, the team scaled the intervention in both the three intervention and three control districts.

Scale-up and transition phase

From the onset, sustainability was a key component of all project plans and design. We involved Ministry of Health and district officials in the research, design, test, and implementation periods of the intervention so IntraHealth could transition the project to districts at the end of the scale-up phase. We utilized a training of trainers model to train district health officials on the intervention who in turn trained health workers and village health teams in each of their districts. This model allowed for ownership at the district level from the beginning of the scale-up phase and created a depth of knowledge throughout the district.

At the end of the scale-up period, the teams connected clients to 7,434 contraceptive methods and contributed to 61.5% of total postpartum family planning uptake in the six project districts.

Why was this approach successful?

There are a multitude of interconnected reasons why an intervention succeeds or “fails.” We’ve picked out a few that we recognized as critical components to improving postpartum contraceptive uptake.

- The intervention was tested during a rigorous research phase and results were disseminated throughout both intervention and control districts. This allowed us to gain significant buy-in from stakeholders, particularly among those who made funding decisions.

- Involving stakeholders from the beginning of the intervention and meaningfully engaging them at each stage of the process made stakeholders feel like they were part of the intervention and led to a natural transition of “ownership” of the intervention.

- The use of behavioral science methods ensured the intervention was relevant, appropriate, and fun for the target community.

- Working with a population that has historically been neglected in this topic area allowed us to amplify our reach.

What’s next?

More scale! One of the benefits of the SupCap model is that all materials developed by the project are publicly available and our team is actively training other organizations and district teams on how they can use and adapt the SupCap approach in their context. In late January of this year, the SupCap program manager worked with Reproductive Health Uganda (RHU) through the WISH2ACTION project to conduct a training of trainers for their cluster teams on the intervention. During the training, the RHU team identified ways in which they could adapt the game to better fit their context (e.g., including content specific to young people and gender-based violence).

To date, 24 clan leaders within RHU’s target communities have been trained on the approach and they continue to hold small group sessions in communities.

We encourage you and your team to explore the materials and reach out if you’re interested in implementing and adapting this intervention in your community.